2 Anterior and Medial Thigh

THE LOWER LIMB

Anterior and Medial Thigh

|

Learning Objectives By the end of the course students will be able to:

|

Reference: Moore, Clinically Oriented Anatomy, Chapter 5

| Particularly relevant Blue Boxes in Moore:●Varicose Veins, Thrombosis, and Thrombophlebitis, p. 540●Saphenous Vein Graphs, p.540● Saphenous Cutdown and Saphenous Nerve Injury, p. 540-1

●Enlarged Inguinal Lymph Nodes, p. 541 ●Regional Nerve Blocks of Lower Limb, p. 541 ●Palpation, Compression, and Cannulation of the Femoral Artery, p. 560 ●Femoral Hernia, p. 561-562 ●Location of Femoral Vein, p. 561 ● Patellar Tendon reflex p. 559

|

To access the Netter Presenter Database click here

Grant’s Dissector, 15th Edition, pp 165 – 176

To access the Gray’s Clinical Photographic Dissector section on the Thigh click here

To access the Primal Pictures software click here

The Primal Pictures model of the Thigh

THE LOWER LIMB

Introduction

The primary function of the lower limb (i.e. inferior extremity) is to provide a means of locomotion through walking (professionally called “gait”). The lower limb must possess strength, stability, and flexibility to serve its function. The anatomy of the lower limb is specialized to accommodate these occasionally conflicting demands. We will see later that the upper limb, whose basic architecture is remarkably like that of the lower limb, has evolved different specializations; sacrificing some of the strength and stability for increased maneuverability (read section in Moore on Posture and Gait, p. 542-544).

The lower limb is divided into three parts: the THIGH, the LEG, and the FOOT. Three joints separate these three parts: the HIP (ball and socket), the KNEE (hinge), and the ANKLE (hinge) joint.

The bones of the lower limb (Moore 512) include the FEMUR, PATELLA, TIBIA, FIBULA, and 26 bones in the foot (Netter 476, 500, 511). The patella is a sesamoid bone, which is a special type of bone found where a tendon crosses a joint. The patella is located in the tendon that passes over the knee joint and acts to protect the tendon and increase its mechanical effect.

These joints allow different movements between the bones of the lower limb. The hip joint is fairly mobile due to its ball and socket construction. The hip movements are grouped into three opposing pairs: flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and medial rotation/lateral rotation. At the knee, there is normally only flexion/extension. The ankle joint allows for two groups of movement, flexion/extension and eversion/inversion. In the ankle, flexion/extension is referred to as plantar flexion/ dorsifexion (read the section in Moore on Terms of Movement, pp. 7 – 11 for definitions and diagrams of these movements).

Our main interest in the lower limb is learning the muscles, which produce various movements across these joints, as well as the nerves and blood vessels that supply them. The muscles of the lower limb can be grouped into discrete compartments. Within each compartment, you will generally find muscles that have the same nerve and vascular supply and produce the same type of movements. There are however, exceptions to this rule and some compartments contain muscles that have different innervations, vascular supplies, and actions.

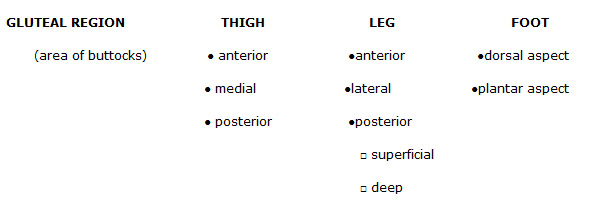

The traditional division of the lower limb musculature results in the following compartments:

It is important to learn the bony attachments of the muscles and the joints they cross in order to understand the actions muscles produce. The muscles of the ANTERIOR THIGH COMPARTMENT cross both the hip and knee joint and attach anteriorly, allowing for extension at the knee joint and flexion at the hip joint. Similarly, the POSTERIOR THIGH COMPARTMENT acts to extend the leg at the hip and flex the leg at the knee because its muscles attach posteriorly to both those joints

We see the same arrangement in the leg. The POSTERIOR COMPARTMENT muscles attach to both the femur and the heel bone (and other foot bones) posteriorly and allow flexion of the leg at the knee joint and plantarflexion of the foot at the ankle joint. The ANTERIOR COMPARTMENT of the leg has no muscle attachments across the knee joint. The muscles of this compartment cross the ankle joint, attaching to the dorsum of the foot and allow dorsiflexion of the foot.

The MEDIAL THIGH muscles adduct the thigh, and the LATERAL LEG muscles evert the foot.

The GLUTEAL MUSCLES, in addition to extending the thigh, abduct and laterally rotate the thigh.

For detailed tables on the muscles of the Lower Limb Compartments reference the relevant Moore Text:

ANTERIOR THIGH: p.546-547

MEDIAL THIGH: p.549

POSTERIOR THIGH: p. 570

GLUTEAL REGION: p.564

ANTERIOR AND LATERAL LEG: p.591

POSTERIOR LEG: p.597-598

FOOT: p. 612-614

Innervation of the Lower Limb(Netter 484, 485; Moore 538)

The nerve supply to all these muscles is straightforward: Each compartment has its own nerve. The nerve fibers that innervate these muscles arise from the LUMBAR or SACRAL segments of the spinal cord. The spinal nerves exit the spinal cord and join into either the LUMBAR (Netter 486) or SACRAL PLEXUS (Netter 487) . Then from the plexus, the nerves group into discrete nerves that supply the lower limb.

|

Netter Plate 484 demonstrates the major nerves to the lower limb as they come off of the spinal cord. In the thigh, there are three large nerves; the FEMORAL NERVE in the anterior compartment, the OBTURATOR NERVE in the medial compartment, and the SCIATIC NERVE in the posterior compartment. The sciatic nerve is the only one of these large nerves that continues beyond the thigh; both the femoral and obturator nerves supply only thigh muscles. The sciatic nerve provides the sole motor supply to the leg and foot. Contained within the sciatic nerve there are two divisions known as the TIBIAL and the PERONEAL nerve(Netter 486, the peroneal nerve is also referred to as the common fibular nerve). Once the divisions separate, the tibial nerve supplies the muscles of the posterior compartment of the leg. The peroneal nerve then further divides into the SUPERFICIAL PERONEAL (a.k.a. FIBULAR) NERVE, supplying the lateral compartment, and the DEEP PERONEAL NERVE, supplying the anterior compartment of the leg. The tibial nerve continues into the foot to become the PLANTAR NERVES, which supply the plantar surface (sole) of the foot. The deep peroneal nerve continues into the foot supplying muscles on the dorsal (superior) surface. The muscles of the GLUTEAL REGION receive their innervation from small nerves which also arise from the lumbo-sacral spinal cord, and pass individually to each of the small muscles in the region. |

Look at the cutaneous innervation of the lower limb shown in Netter’s Plate 469. This diagram demonstrates the approximate patterns of nerve representation according to spinal cord levels (also known as a dermatome map). Note that the T12/Ll border is roughly along the inguinal ligament and the lower sacral (and coccygeal) portions are centered in a small area around the anus and genitalia.

|

Regions of Lower Limb and Their Main Source of Motor Innervation – SUMMARY ANTERIOR THIGH = FEMORAL nerve MEDIAL THIGH = OBTURATOR nerve POSTERIOR THIGH = SCIATIC (TIBIAL & COMMMON. PERONEAL) nerve POSTERIOR LEG = TIBIAL nerve LATERAL LEG = SUPERFICIAL PERONEAL nerve ANTERIOR LEG = DEEP PERONEAL nerve |

Blood Supply to the Lower Limb

Blood leaving the heart travels inferiorly within the very large AORTA through the thorax (chest) and abdomen. The aorta divides into LEFT and RIGHT COMMON ILIAC ARTERIES, each of which then divides into an EXTERNAL and an INTERNAL ILIAC ARTERY (Netter 376).

The internal iliac artery is the main blood supply to the pelvis. The pelvis is the most inferior portion of the body cavity and contains the urogenital organs, distal colon, and rectum. The internal iliac artery additionally supplies the medial thigh and gluteal regions via the OBTURATOR and GLUTEAL ARTERIES, respectively (Netter 376, 379).

The major blood supply to the lower limb is the EXTERNAL ILIAC ARTERY. As soon as it leaves the pelvis and enters the thigh, it is renamed the FEMORAL ARTERY. The femoral artery gives off a large branch, known as the DEEP FEMORAL ARTERY, which is the main arterial supply of the thigh.

|

The femoral artery travels inferiorly and medially through the anterior compartment of thigh. It then passes through the thigh and enters the posterior region of the knee, where it is renamed the POPLITEAL ARTERY (Netter 489, 505). The popliteal artery is a direct continuation of the femoral artery. Distal to the region of the knee joint, the popliteal artery divides into an ANTERIOR TIBIAL and a POSTERIOR TIBIAL ARTERY. The anterior tibial artery passes immediately to the anterior compartment of the leg. The posterior tibial artery gives off a branch, the PERONEAL ARTERY, and both the posterior tibial and peroneal arteries supply blood to the posterior compartment of the leg. |

The main arterial supply to the foot is from the PLANTAR ARTERIES (Netter 522), which are continuations of the posterior tibial artery. The final segment of the anterior tibial artery is called the DORSALIS PEDIS ARTERY and supplies the dorsum of the foot (Netter 518).

Fascia of the Lower Limb (Netter 471, 472)

The musculature of the entire lower limb is invested in a thick fibrous stocking of connective tissue, known as the DEEP FASCIA. The deep fascia of the thigh is called the FASCIA LATA and as it continues onto the leg it is called the CRURAL FASCIA. The deep fascia of the foot forms two important specializations: the various RETINACULA (singular retinaculum) and the PLANTAR APONEUROSIS. Retinacula are fibrous thickenings of fascia that wrap around the ankle to hold the tendons, vessels, and nerves in place as they pass into the foot. The plantar aponeurosis is a tough, fibrous, thickening on the sole of the foot. Immediately superficial to the deep fascia is the SUPERFICIAL FASCIA, which is a mixture of fibrous connective tissue and fat cells. Running through this layer are the CUTANEOUS NERVES and SUPERFICIAL BLOOD VESSELS that supply the SKIN. The skin is immediately superficial to the superficial fascia.

|

Running the entire length of the lower limb, from foot to proximal thigh, is the GREAT SAPHENOUS VEIN (Netter 472). This very important vein runs through the superficial layer and is the longest vein in the body. It ascends along the medial aspects of the leg and thigh and pierces through the fascia at a hole called the FOSSA OVALIS. Superficial lymph nodes run along the ascending superficial veins to connect with superficial inguinal lymph nodes along the inguinal ligament. |

Clinical Correlation: The great saphenous vein accompanies the saphenous nerve, which is vulnerable to injury when it is harvested surgically. It is commonly used for coronary artery bypass surgery, and the vein should be reversed so its valves do not obstruct blood flow in the graft. This vein and its tributaries may become varicosed and dilated.

Thrombophlebitis is a venous inflammation with thrombous formation that occurs in the superficial veins in the lower limb, often leading to pulmonary embolism. However, most pulmonary emboli originate in deep veins, and the risk of embolism can be reduced by anticoagulant treatment.

Varicose veins develop in the superficial veins of the lower limb because of reduced elasticity and incompetent valves in the veins or thrombophlebitis of the deep veins.

OSTEOLOGY – LOWER LIMB

It is beyond the scope of this syllabus to discuss all the features of these bones. You should read the discussion of the hipbone, femur, tibia, and fibula in your text (Moore pp. 512-530, Netter 473, 474 ,475, 476, 477,478, 499)

|

Important structures: Hip Bone Femur Tibia Fibula Ilium Head Med & Lat. Condyles Head Ischium Neck Sup. Articular surfaces Lateral malleolus Ischial tuberosity Trochanters Medial malleolus Pubis, pubic tubercle Shaft, linea aspera Acetabulum Med.& Lat. Epicondyles Med.& Lat. Condyles |

The Femoral Triangle(Netter 479, 480, 487, 488, Moore 551)

The FEMORAL TRIANGLEis an anatomical area of the anterior proximal thigh. When discussing the femoral triangle it is important to know its boundaries and contents. The femoral triangle boundaries consist of three sides-superior, medial, lateral, a roof, and a floor.

Boundaries:

Superior: The inguinal ligament (Poupart’s ligament) is a band of connective tissue

which runs from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the pubic tubercle

Lateral: The sartorius muscle originates at the ASIS and inserts at the medial condyle of the tibia. The medial border of this muscle serves as the lateral boundary of the triangle.

Medial: The adductor longus muscle originates near the pubic symphysis and attaches to the linea aspera. The medial border of this muscle is the medial border of the femoral triangle.

Roof: The roof is formed by the fascia lata, the deep fascia of the thigh. In the femoral triangle, the fascia lata splits to form an oblique opening, the fossa ovalis. This opening allows the superficial Great Saphenous Vein to pass through the fascia lata and join the deep femoral vein.

Floor: The floor is made by the iliopsoas, pectineus, and adductor longus muscles. The iliopsoas muscle is a combination of the iliacus and psoas major muscles. It enters the thigh deep to the inguinal ligament and inserts on the lesser trochanter of the femur. The pectineus and adductor longus muscles belong to the adductor group in the medial thigh compartment. These muscles originate from the pubic bone and insert on the linea aspera, which is located on the posterior femur.

Inguinal Ligament (Netter 488)

The INGUINAL LIGAMENT is formed by the aponeurotic fibers of the external oblique muscle. The ligament stretches from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the pubic tubercle. At the medial end of the inguinal ligament, fibers reflect backwards to insert into the superior ramus of the pubis, which forms the lacunar ligament. The iliopsoas muscle and the femoral vein, artery, and nerve all pass below the inguinal ligament. The inguinal canal passes obliquely through the abdominal wall above the ligament.

The femoral nerve arises from the lumbar spinal nerves L2, L3, L4, and runs deep to the iliacus fascia. It passes through the pelvis and deep to the inguinal ligament, finally emerging into the anterior thigh region. In the thigh, it divides into muscular branches giving off nerves to the anterior muscle group of the thigh as well as cutaneous branches to the anterior and medial thigh.

The femoral artery, femoral vein, and the lymphatic vessels enter the thigh in the femoral sheath (but not the femoral nerve). This sheath is a continuation of the connective tissue lining the abdomen and pelvis (transversalis fascia). The connective tissue forms a tube of fascia, which runs deep to the inguinal ligament. This sheath is divided further into three parallel tubes, one for each structure contained within it (artery, vein, and lymphatics). The most medial division, which carries the lymphatics, is called the FEMORAL CANAL.

The proximal, or pelvic end of the femoral canal is known as the femoral ring. The femoral ring, similar to the femoral triangle, has boundaries that are:

Medial: lacunar ligament

Posterior: pectineal ligament

Lateral: the femoral vein,

Anterior: the inguinal ligament.

The important contents of the femoral triangle include the femoral Nerve, femoral Artery, femoral Vein, and assorted Lymph nodes. These structures pass deep to the inguinal ligament and deep to the inguinal canal to enter the anterior thigh. Note the mnemonic NAVL, which from lateral to medial, indicates the relation between these four structures within the femoral triangle space.

|

Clinical Consideration: 1. A femoral hernia passes through the femoral ring and canal and lies lateral and inferior to the pubic tubercle and deep and inferior to theinguinal ligament. They are more common in women than in men because of their generally wider pelvises. Strangulation of a femoral hernia may occur because of the sharp stiff boundaries of the femoral ring and the strangulation interferes with the blood supply to the herniated intestine, resulting in necrosis. see Blue Box in More p. 561 2. The femoral pulse is palpated just below the inguinal ligament, roughly halfway between the ASIS and the pubic tubercle (Blue Box p. 560). 3. Catheters may be placed into the femoral vein and passed up into the aorta to measure blood pressure or to inject contrast material for radiographic studies (Blue Box p. 561). A video showing the placement of a femoral venous catheter may be found by clicking here (from the New England Journal of Medicine’s series of Videos in Clinical Medicine) |

ANTERIOR THIGH(Netter 479, Moore pp. 545-548)

The anterior thigh muscles generally extend the leg at the knee. The muscles that cross the hip joint can also flex the thigh. All of these muscles are innervated by the femoral nerve and their major blood supply comes from branches of the deep femoral (profunda femoris) artery.

The muscles of the anterior thigh are (See Table 5.3.1 in Moore):

- Sartorius

- Rectus Femoris

- Vastus Medialis

- Vastus Lateralis

- Vastus Intermedialis

- iliopsoas

The sartorius muscle originates from the ASIS and inserts on the upper medial aspect of the tibia. Its function is to flex both the hip and the knee. In addition to flexion, this muscle allows for adduction and laterally rotation the thigh; all of which results in “crossing the leg”.

The quadriceps muscle group is formed by the rectus femoris and the three vasti muscles. Rectus femoris originates from the hipbone by two muscular heads; one from the Anterior Inferior Iliac Spine (AIIS) and one from the acetabular rim. The vasti muscles all originate from the shaft of the femur. All four muscles insert via a common tendon known as the quadriceps tendon. The quadriceps tendon inserts onto the proximal anterior tibia and allows the muscles to produce powerful extension at the knee. The patella, a sesamoid bone, is found within the quadriceps tendon as it crosses the knee joint.

Extension of the leg at the knee is accomplished by the anterior group consistnig of the quadriceps femoris with the assistance of the tensor fascia lata. Because the rectus femoris crosses the hip and knee joints (flexing the thigh at the hip and extending the leg at the knee) its efficiency at one joint depends on the position of the other joint. Thus, when the hip is extended, the rectus femoris is stretched and its for-generating capacity to extend the knee is greatest.

The iliopsoas muscle (Netter 483) , the combined muscle of the psoas major and iliacus, is a major flexor of the thigh at the hip. The psoas major unites with the iliacus at the level of the inguinalligament and crosses the hip joint to insert on the LESSER trochanter of the femur. The psoas major is supplied by direct branches of the lumbar plexus (Netter 485) at the levels of L1 and L2 while the iliacus is innervated by the femoral nerve (L2 – L4)

The anterior compartment is separated from the medial and posterior compartments by intermuscular septi (Netter 492).

Blood Supply to Thigh (Netter 487, 488, Moore, p. 554)

The predominant vascular supply of the anterior thigh comes from branches of the deep femoral artery (DFA). This artery is a branch off of the femoral artery near the apex of the femoral triangle. The DFA has several important branches, which include: the lateral and medial femoral circumflex arteries and various perforating branches. The lateral and medial circumflex arteries wrap around the femur to supply the cruciate anastomosis (cross-shaped) and much of the hip area. The perforating branches wrap around the femur as the DFA descends to supply most of the thigh muscles.

After the DFA branches off, the femoral artery continues on as the superficial femoral artery, supplying little blood to the thigh. It descends through the thigh in the adductor canal, passing through the adductor hiatus (an opening in the adductor magnus muscle) to enter the popliteal fossa. Here the artery is renamed the popliteal artery (Netter 505).

The adductor canal is a tunnel that begins at the mid-thigh region and ends at the adductor hiatus. It is bounded laterally by the vastus medialis, posteriorly by the adductor muscles, and is covered superficially by the sartorius.

|

Summary of Blood Supply to Anterior Compartment of Thigh (Netter 487, 488) The femoral artery is the principal supply to the anterior compartment of the thigh, as well as the rest of the lower limb. Its branches are:

The femoral artery changes its name to become the popliteal artery after it passes through the adductor hiatus. |

|

Clinical Considerations 1. The quadriceps deep tendon reflex (patellar reflex) is elicited by briskly striking the quadriceps tendon with a rubber hammer. This impact results in a stretching of the quadriceps muscles and the nervous system responds to this quick stretching with a brief impulse, which causes the quadriceps to contract (knee-jerk reflex, Blue Box p. 559). 2. Occlusion of the femoral artery may occur in the region of the adductor canal. This may be caused by increased pressure on the artery from the ischiocondylar portion of adductor magnus muscle (this portion forms the adductor hiatus). The medial femoral circumflex artery is clinically important because its branches run through the neck to reach the head and it supplies most of the blood to the neck and head of the femur except for the small proximal part that receives (in younger people) blood from a branch of the obturator artery. The femoral artery is easily exposed and cannulated at the base of the femoral triangle just inferior to the midpoint of the inguinal ligament. The superficial position of the femoral artery in the femoral triangle makes it vulnerable to injury by laceration. When it is necessary to ligate the femoral artery, the cruciate anastamosis supplies blood to the thigh and leg. The cruciate anastamosis of the buttocks is formed by an ascending branch of the first perforating artery of the deep femoral artery, the inferior gluteal artery and the transverse branches of the medial and lateral femoral cricumflex arteries. The cruciate anastamosis bypasses an obstruction of the external iliac or femoral artery. |

MEDIAL THIGH(Netter 480, Moore p. 548-551)

The medial compartment of the thigh is frequently called the adductor compartment because the major action of these muscles is adduction. One exception to this grouping is the hamstring (ischiocondylar) portion of the adductor magnus. This muscle functions as a hamstring muscle and is supplied by a different nerve than the rest of the medial compartment. Some people also include the pectineus with this group of muscles, but it really belongs to the anterior compartment and is innervated by the nerve of the anterior compartment.

The adductor compartment of the medial thigh contains 5 muscles (see Table 5.4 on Moore):

- Gracilis

- Adductor Longus

- Adductor Brevis

- Adductor Magnus

- Obturator Externus

|

The adductor magnus is actually divided into superior, middle, and inferior portions. The superior and middle portions are true adductors and receive their innervation from the obturator nerve. In addition to adducting the femur, they also flex and medially rotate it. The inferior, or ischiocondylar portion, inserts on the adductor tubercle of the femur and is essentially one of the hamstring muscles. This portion receives its innervation from the tibial division of the sciatic nerve. In addition to adducting the femur, the ischiocondylar portion of the adductor magnus extends and laterally rotates it. |

All of these muscles receive motor innervation from the obturator nerve. The obturator nerve arises from the lumbar spinal nerve roots L2, L3, and L4. This nerve leaves the pelvis via the obturator foramen and divides into anterior and posterior branches. The anterior branch lies between and supplies both the adductor longus and brevis muscles. The anterior branch also innervates the gracilis muscle. The posterior branch lies deep to the fascia of the adductor magnus and supplies the adductor portion of the muscle.

Clinical Considerations:

A groin injury or pulled groin is a strain, stretching or tearing of the origin of the flexor and adductors of the thigh and often occurs in sports that require quick starts. The gracilis is a relatively weak member of the adductor group of muscles and thus surgeons often transplant this muscle or part of it, with nerve and blood vessels, to replace a damaged muscle in the hand.

Muscle strains of the adductor longus may occur in horseback riders and produce pain because the riders adduct their thighs to keep from falling off.

Anterior and Medial Thigh Quiz – click here