3 Week 2: GI Bleeding (Week of 3/13/2023)

DISCUSSION SESSIONS WEEK OF 3/13/2023

Assignments Due: 3/14/2023 @ 8AM

Prior to Class

- Watch Canvas video lecture, “Pretest Probability”.

- Read syllabus section on GI bleeding (below).

- Complete the required quiz (Quiz A) on Canvas.

- Complete pre-class case, Mrs. Herrera.

- Prepare answers to the below discussion question based on the pre-class case:

- What are the key features of the clinical history and exam that make an upper source of gastrointestinal bleeding more likely?

- If assigned, complete the Self-Directed Learning Assignment and send to small group faculty leader.

Learning Objectives

- Describe illness scripts

- Define pre-test probability and describe how it is used in the diagnostic process

- Identify the common causes of GI bleeding by learning the illness script patterns for each.

- Build a prioritized differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with GI bleeding that includes the common and life/function threatening causes.

- Identify the components of the history and physical, as well as the laboratory and radiological findings, crucial for correctly diagnosing a patient presenting with GI bleeding

BUILDING ILLNESS SCRIPTS

Developing accurate and detailed illness scripts is the most important step in developing clinical reasoning abilities. The more a clinician knows about the underlying diseases, the more likely they are to be able to “match” the problem representation to an illness script. Although in this course we approximate illness scripts with the handouts listing the key features of the covered diseases, in reality illness scripts are largely unconscious having been built up over years of clinical experience and study. Experienced clinicians know far more about the diseases than they can recall and write down. These unconscious illness scripts are “activated” into consciousness by the data coming in for a specific patient. A clinician, for example, may have variceal bleeding pop into their mind as soon as they hear about a patient with cirrhosis presenting with hematemesis and hemodynamic instability. Although other things can certainly cause this constellation of findings, the clinician has seen many patients with variceal bleeding present this way and it is part of their illness script for variceal bleeding.

Good illness scripts include not only the key findings associated with a disease, but also a marker of the strength of association between the findings and the disease. The presence of anemia, for example, is an important component of most causes of gastrointestinal bleeding, but it does little to differentiate among the various causes of bleeding. The presence of NSAID use, however, is more tightly linked to peptic ulcer disease just as cirrhosis is predictive of a variceal bleed. Sometimes these associations are also somewhat opaque, such as the importance of knowing about prior aortic surgery in assessing the possibility of an aortoenteric fistula. Likelihood ratios are an excellent means of determining the strength of association between a finding and a disease and are a critical component of robust illness scripts.

We will use cases to help build your illness scripts, but studying the findings associated with the diseases will be necessary to further build your abilities. One important and evidence-based way to develop illness script knowledge is to compare and contrast at least three diseases at once in order to emphasize which clinical findings distinguish one disease from another. The diagnostic reflections built into the preclass cases are an example of how to do this.

PRETEST PROBABILITY

Pretest probability is the probability of a disease before a test is done. Note that a “test” can be an element of the history or physical exam as well as laboratory and imaging findings. Pretest probability is based on the information known at that time and may be as limited as the epidemiology of a certain disease in a given population. Prediction rules are useful tools that provide mathematical calculations of probability of a disease from the literature. These come from large databases and use base rates of disease and clinical findings to help predict the probability of disease in a given situation. The most famous prediction rule is probably the Wells score for pulmonary embolism. The prediction rules are frequently used in clinical practice to help estimate the likelihood of disease in a given patient.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a common medical condition among patients presenting to the emergency department or hospital. When encountering these patients, it is crucial to quickly distinguish between upper GI (UGI) and lower GI (LGI) sources of bleeding, as the differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management for these two conditions are very different. UGI are more often severe than LGI bleeds, although both UGI and LGI bleeds can represent life-threatening emergencies.

UGI bleeding originates from sources proximal to the ligament of Treitz. Features of UGI bleeding typically include hematemesis, coffee-ground emesis, and melena. Hematemesis is the vomiting of bright red blood while coffee-ground emesis is the vomiting of blood that has been acted upon by the acid in the stomach and which looks like coffee grounds. Melenic stools are usually dark black, sticky, and foul-smelling and represent digested blood. Of note, hematemesis may not be present if patients are experiencing intermittent UGI bleeding or a bleeding source in the distal duodenum. In addition, melena, although usually representative of an upper source, may also rarely result from a very slow bleed in the small intestine or proximal colon.

LGI bleeding originates from sources distal to the ligament of Treitz. Hematochezia (frank blood) and bloody or maroon-colored stools are typical for LGI bleeds. Of note, a very rapid UGI bleed may also result in hematochezia (about 10% of patients with hematochezia have an upper source of bleeding and are often profoundly ill).

Due to the overlap of signs between UGI and LGI bleeds, a thorough initial history and physical exam, including the identification of alarm symptoms, are essential to guide diagnosis and management. Important factors include vital signs (including orthostatics), evidence of ongoing bleeding, and noteworthy risk factors, such as history of liver disease or NSAID use. Alarm symptoms include dizziness or lightheadedness, which may suggest significant blood loss, and chest pain or shortness of breath, which may suggest cardiac ischemia secondary to significant blood loss.

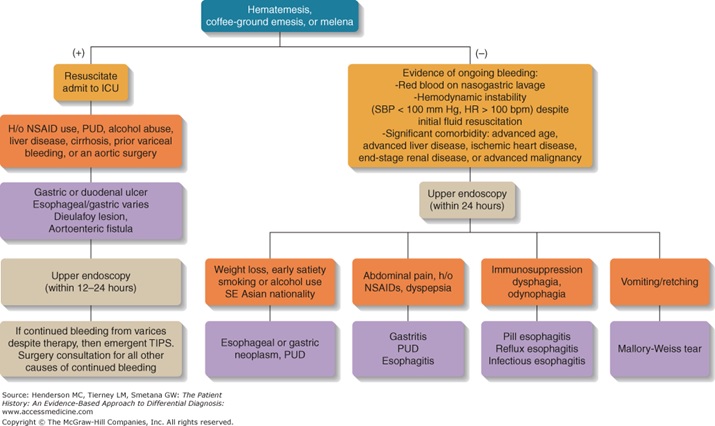

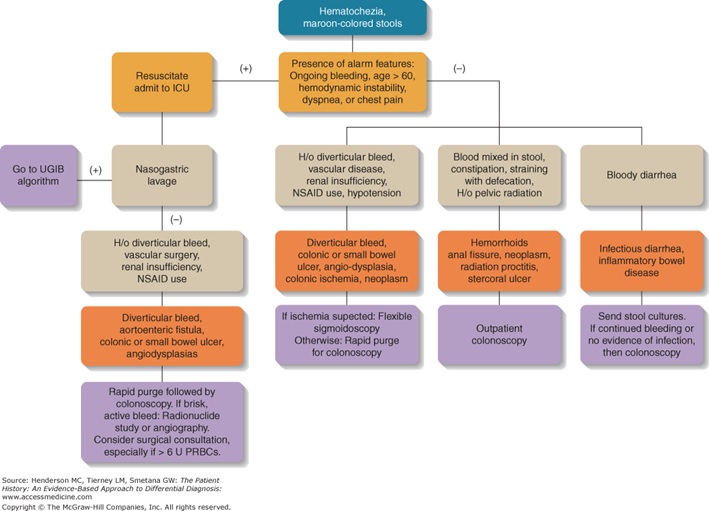

An Algorithmic Approach to GI Bleeding

Below are two algorithms that are helpful in considering the differential diagnosis for UGI and LGI bleeds.

Resources for Further Reading

- Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, “Gastrointestinal Bleeding”

- Symptom to Diagnosis: An Evidence-Based Guide, “I have a patient with GI Bleeding. How do I determine the cause?”