10 Week 7: Syncope (Week of 9/11/2023)

Week 7: Syncope

DISCUSSION SESSIONS Week of 9/11/2023

Assignments Due: 9/12/2023 @8AM

PRIOR TO CLASS

- Read syllabus section on syncope (below).

- Complete the required quiz (Quiz F) on Canvas.

- Complete pre- class case, Mr. Martins.

- Prepare an answer to the below discussion question and be prepared to discuss when you come to class:

- What aspects of Mr. Martin’s presentation support the diagnosis of vasovagal syncope as opposed to another cause of syncope?

- If this is your assigned week, complete the Self-Directed Learning Assignment and submit via email to your faculty member any time before your group session.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the concept of causal reasoning and its importance to the diagnostic process.

- Apply causal reasoning to the diagnostic process.

- Build a prioritized differential diagnosis for syncope that includes common and life/function threatening diagnoses.

- Identify the components of the history and physical, as well as the laboratory and radiological findings, crucial for correctly diagnosing a patient presenting with syncope.

CAUSUAL REASONING

Causal reasoning is an excellent means of assessing the likelihood of a potential diagnosis. In using causal reasoning, you try to determine whether a proposed diagnosis can explain the findings of the clinical presentation in physiological and pathophysiological terms. For example, in a patient with pneumonia, the clinical findings are easily explained. Cough is due to bronchial irritation secondary to hyper-secretion of mucus in response to infection. Sputum is the product of bronchial gland cell response to infection. Fever results from pyrogenic cytokine production secondary to leukocyte activation. Leukocytosis is a cellular response to infection. A lobular infiltrate on chest X-ray demonstrates that alveoli are filled with pus and thus appear with increased density on radiography.

Causal reasoning is a form of analytic reasoning, as it is conscious and requires effort. It is, however, an important step in the diagnostic process and can help evaluate whether or not a proposed diagnosis is the most likely one. In the event that causal reasoning cannot explain a finding, an alternate explanation, second diagnosis, or new diagnosis may need to be considered. This approach is an important guard against search satisficing. Search satisficing occurs when we stop our search when we are satisfied that the probability of a diagnosis suffices. This often occurs even in the face of data that does not fit the diagnosis we’ve chosen. Because our brains are cognitive misers, we tend not to be comprehensive in our search and call it off once we find a diagnosis that is good enough, even if it is not a very good explanation for the clinical findings.

SUTTON’S LAW

Willie Sutton was a bank robber who, when asked by a reporter why he robbed banks, supposedly said, “because that’s where the money is”. In his autobiography, Sutton denies ever having said this. Instead, he said he robbed banks because he enjoyed doing it. Nevertheless, Sutton’s Law has been named after his alleged statement….”Go where the money is.” Applied to the diagnostic process, it urges us to pursue the line of diagnosis most obviously suggested by currently available clinical information. When a patient has many non-specific symptoms that make choosing a direction difficult, try to focus on one specific symptom, often the one that is most concerning to you or the patient. For example, in a patient with vague symptoms who is most concerned by his diarrhea, you may consider stool testing or a colonoscopy as a next high yield step in establishing a diagnosis.

You may also focus on one sign or symptom that is specific to a small number of potential etiologies. In evaluating a patient with nausea and hematochezia, for example, focusing on the nausea may be difficult because it is a relatively non-specific symptom, being caused by everything from pregnancy to myocardial infarction to gastroenteritis. Hematochezia, however, has a much more limited differential diagnosis and focusing on it rather than the nausea is a good idea.

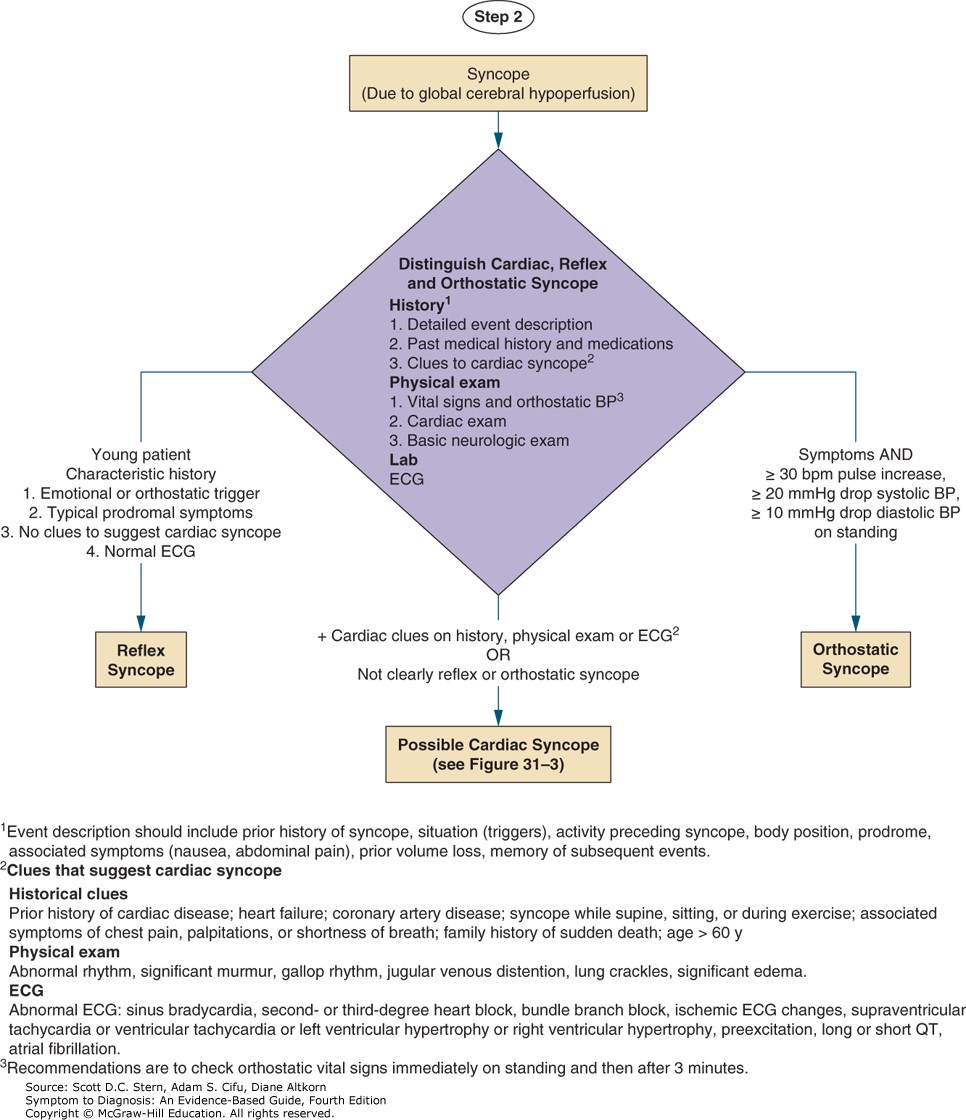

SYNCOPE

Syncope is the term for a transient loss of consciousness or, more colloquially, when a patient “passes out”. It is usually secondary to cerebral hypoperfusion. There are other causes of transient loss of consciousness that are not the result of cerebral hypoperfusion (such as traumatic brain injury and seizures) and these disorders also need to be considered in evaluating a patient with loss of consciousness. Importantly syncope refers to transient loss of consciousness; patient who remain unconscious are not considered to have syncope. Syncope can be caused by multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms and because of this, is a great example of how causal reasoning can help direct and inform the diagnostic process.

Causes of Syncope

ORTHOSTATIC SYNCOPE

Orthostatic syncope occurs when a patient is unable to maintain cerebral perfusion when rising to a seated or standing position. It may be secondary to a wide variety of pathophysiologic causes including autonomic insufficiency (e.g., Parkinson disease), decreased intravascular volume (e.g., bleeding, diuresis), or decreased arterial tone (e.g., vasodilators, anti-hypertensives). Patients often report a prodrome of lightheadedness upon standing and usually do not have persistent symptoms upon awakening, although they may remain relatively hypotensive. Orthostasis may be demonstrated if vital signs are taken in the lying, sitting and standing positions.

CARDIAC ARRHYTHMIA

Cardiac arrhythmia is among the most ominous causes of syncope as recurrence may result in sudden death. It may occur as the result of bradycardia (such as high-grade atrioventricular block) or tachycardia (such as ventricular tachycardia). It is most common in patients with pre-existing cardiac disease, but can occur in patients who otherwise appear healthy. Patients with cardiac arrhythmia as a cause of syncope often have no prodrome (or a very brief one) before losing consciousness and tend not to have persistent symptoms upon awakening.

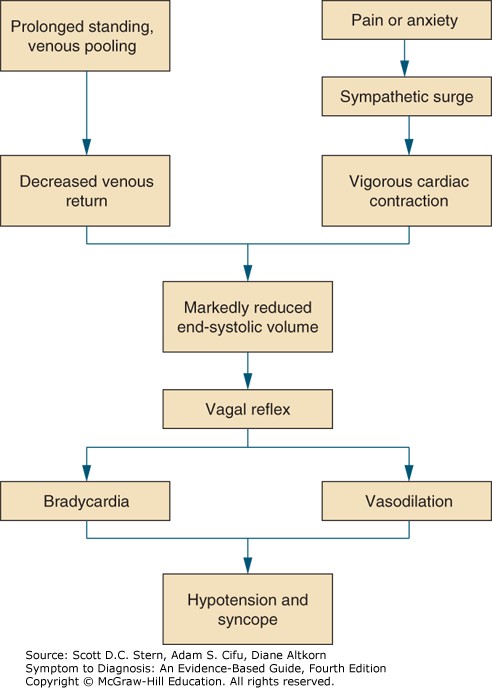

REFLEX SYNCOPE

Reflex syncope refers to loss of consciousness that results from the combination of a decreased sympathetic tone (called the vasodepressor response) and increased parasympathetic activation (the cardioinhibitory response). The mechanisms that cause changes in these responses are complex and involve multiple different receptors and reflexes. Major types of reflex syncope include vasovagal syncope (the “common faint”), carotid sinus hypersensitivity, and situational syncope (e.g., with micturition or defecation). Reflex syncope, especially vasovagal syncope, is often associated with a prodrome of nausea, diaphoresis, and palpitations. Upon awakening, patients continue to feel unwell afterwards and are often nauseated and fatigued. The pathophysiology of reflex syncope is depicted below.

OBSTRUCTIVE SYNCOPE (STRUCTURAL CARDIOPULMONARY DISEASE)

Obstructive syncope occurs because there is a specific and structural reason for decreased cerebral blood flow. Causes include pulmonary embolism (blocking flow through the pulmonary arteries), aortic stenosis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (blocking flow through the aortic valve/outflow tract), pericardial tamponade (preventing venous return/filling), and atrial myxoma. There are often symptoms or signs relating to the underlying disease that suggest obstructive syncope, such as dyspnea or chest pain in a patient with pulmonary embolism. It is important to recognize that carotid artery stenosis does not cause syncope, but rather results in focal neurologic deficits.

AN ALGORITHMIC APPROACH TO SYNCOPE