15 Week 11: Low Back Pain (Week of 11/13/2023)

DISCUSSION SESSIONS WEEK OF 11/13/23

Assignments Due: 11/14/2023 @8:00 AM

Prior to Class

- Read syllabus section on low back pain (below).

- Complete the required quiz (Quiz J) on Canvas.

- Complete pre-class case, Mr. Wood.

- Prepare answers to discussion questions on pre-class cases (emailed when case opens on Canvas).

Learning Objectives

- Develop skills necessary to facilitate taking the history and conducting the physical during a challenging physician-patient interaction.

- Identify how affective bias can impact or impair decision making.

- Build a prioritized differential diagnosis for back pain that includes common and life/function threatening diagnoses.

- List the key red flags of the history for low back pain

- Identify the key history, physical exam, laboratory, and radiological findings that are useful in the evaluation of patients with low back pain.

The Challenging Physician-Patient Interaction

Every physician will encounter patients who have characteristics or behaviors that complicate patient care. Difficult interactions with patients are a common scenario in acute care medicine and can threaten our ability to obtain an accurate history and physical exam. Patient factors that may influence care may include patients being upset, frightened, or in pain, communication barriers, intoxications, cognitive impairment, and psychiatric disorders. These situations, while challenging, can be managed by the clinician who controls their emotions and seeks help when necessary.

Most patients don’t consciously choose to be challenging. The astute clinician must recognize when a physician-patient interaction is not going well and try to figure out why. It is essential to remain focused during the patient evaluation, even when challenges arise. In order to avoid misdiagnosis, delays in diagnosis and mistreatment, key elements of the history and physical must be retrieved. The strategies discussed below may be helpful in gathering this information.

- Be sure the patient is able to participate in the conversation. Ask yourself the following questions: Can the patient hear you, or does he/she need a hearing aid? Does he/she understand English, or should you use an interpreter? Is the patient cognitively impaired, and if so, does this need to be addressed? Will you need to rely on someone else to obtain critical elements of the history?

- Don’t be afraid to be direct. If the patient seems upset, it is good practice to ask them if you’ve said something to make them feel that way. Considering your role might make the patient less defensive (e.g., “You seem angry. I may have said something to upset you. How can I remedy this situation?”). If the encounter isn’t going smoothly, it may be because the patient is afraid or in pain. There may be additional information you can gather or action you can take that will make the patient more comfortable. It’s important to let the patient know that you must obtain precise information in order to give them the best possible care.

- If the patient is in distress, a lengthy interview may be more than they can handle. You may need to limit your questions to the essentials. Performing the H&P in a stepwise fashion, getting information from family members and the patient’s chart, and giving the patient a break are all reasonable strategies.

- In rare cases, attempts to gather an H&P will be ineffective no matter what you do. When you sense that things are going very poorly or if a patient becomes overtly hostile and confrontational or refuses to proceed, consider getting someone else involved. You can directly communicate to the patient that you feel the encounter is not going well and ask if they’d like you to find someone else to help.

Keep in mind that some cases don’t have a simple solution.

Challenges in Clinical Reasoning

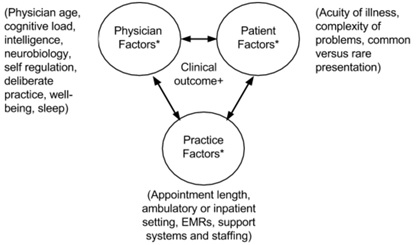

The role of the patient and the emotions a patient may evoke in a clinician illustrates that clinical reasoning is hard in part because so many variables are in play. As depicted in the figure below, factors specific to the clinician, the patient and the environment may all affect the clinician’s reasoning.

Factors related to clinicians themselves may include high levels of stress, overwork, burn-out, poor communication skills, low level of experience, and discomfort with uncertainty, especially early in one’s career. Health care system or other environmental factors may include limited time with patients, changes in health care financing, and the availability of outside information sources that challenge the physician’s authority, such as WebMD. Finally, and as described above, there are many patient factors that may come into play. It is important for clinicians to acknowledge the role of all of these factors that may influence clinical reasoning.

Affective Bias

When physicians are distracted, angry, rushed, or tired, the patient evaluation can be compromised. Like patients, our ability to make rational and accurate decisions can be influenced and impaired by emotion. All decisions have emotional content, either unconscious or overt. Our behaviors, and therefore our decisions, are not necessarily the same for all patients. We may act differently when dealing with patients we like versus those who challenge us. Affective bias describes a situation during which clinical decisions are altered or impaired by emotion and inappropriate value judgments.

In challenging situations, frustration or anger may lead clinicians to curtail their history and physical examination, to get out of the room quickly, or to discharge a patient without a complete evaluation. At worst, negative emotions can lead a clinician to miss a critical finding or diagnosis. Additionally, if we positively identify with a patient, we may fail to order uncomfortable, but necessary, tests or to consider more serious diagnoses as we do not want harm to come to the patient.

No one is immune to affective bias. The key is to recognize when this is occurring, and that decisions are being impacted. In other words, we need to be self-aware. Physicians should always ask themselves if there is something about a patient that is affecting or impairing their ability to make good decisions. This process of thinking about our thinking and feelings is called metacognition. If we don’t use metacognition, the patient may suffer the consequences. When a physician feels that their emotions are clouding their judgment, they shouldn’t hesitate to seek support from peers or professional care.

Approach to Low Back Pain

When evaluating back pain, it is fundamental to understand its epidemiology. Low back pain is one of the most common reasons patients seek medical attention in the United States. In fact, nearly three quarters of adults will develop low back pain within their lifetime. The majority of these cases, about 85%, resolve spontaneously with rest and symptomatic treatment. However, the challenge is to identify the rare patient with low back pain who is harboring a serious medical condition. Because specific causes, such as anatomically-defined lesions, are rare, misdiagnoses and delays in diagnosis of these conditions are common. In your quest for an accurate diagnosis, it is useful to answer two fundamental questions:

- Is the back pain a result of a serious systemic disease, such as malignancy or infection?

- Is there neurological compromise?

The table below is useful for evaluation of low back pain, especially that which may be related to a serious medical condition.

| Table. Pivotal points and clinical clues in the diagnosis of low back pain. Adapted from: Symptom to Diagnosis: An Evidence-Based Guide. | |

| Diagnosis | Pivotal Points & Clinical Clues |

| Cauda equina syndrome | Urinary retention, saddle anesthesia, bilateral leg weakness, bilateral sciatica |

| Infection | Fever, recurrent skin or urinary tract infection, immunosuppression, injection drug use |

| Malignancy | Cancer history (especially currently active cancer), unexplained weight loss, age >50, duration >1 month |

| Compression Fracture | Age >70, female sex, corticosteroid use, history of osteoporosis, trauma |

| Lumbar-radiculopathy | Sciatica, abnormal neurological exam |

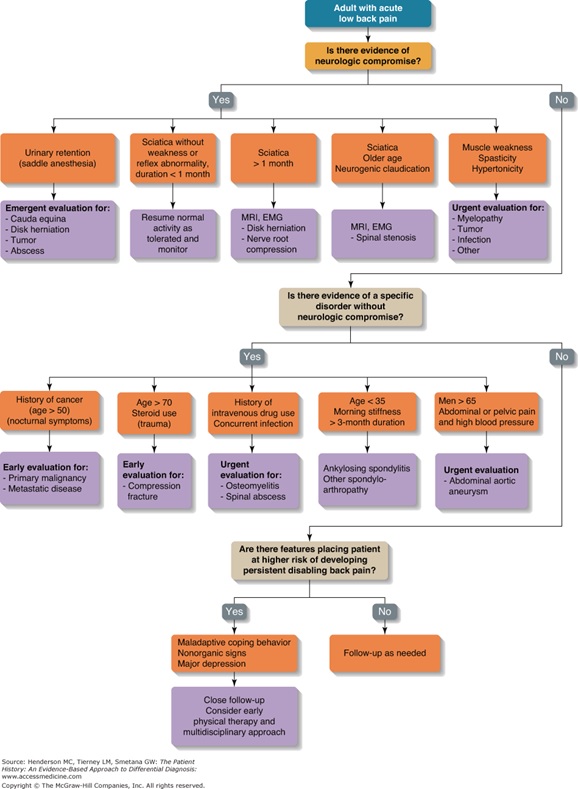

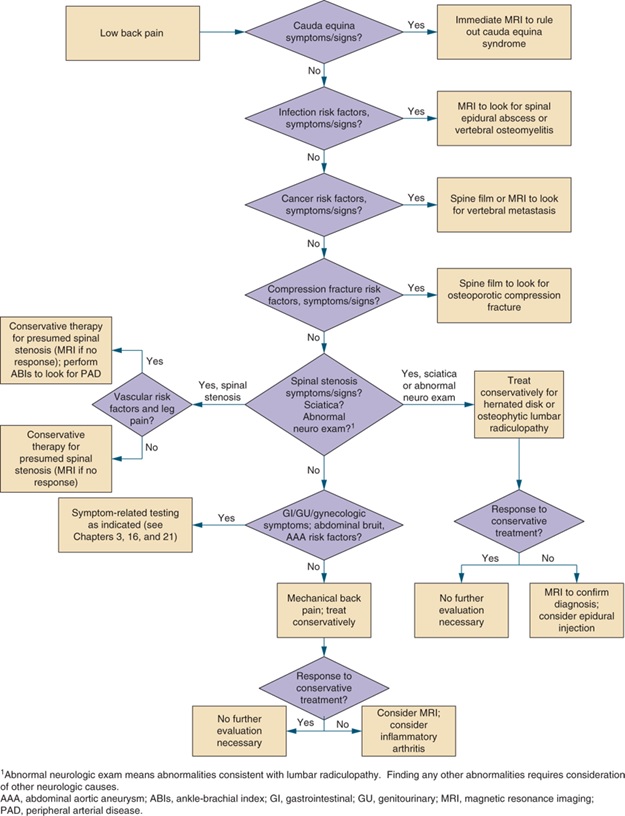

An Algorithmic Approach to Low Back Pain

Resources for Further Reading

- Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, “Back and Neck Pain”

- UpToDate, “Evaluation of low back pain in adults”