7 Week 5: Dyspnea (Week of 4/29/2024)

Week 5: Dyspnea

DISCUSSION SESSIONS WEEK OF 4/29/24

Assignments Due: 4/30/2024 @8:00AM

PRIOR TO CLASS

- Read syllabus section on dyspnea.

- Complete the required quiz (Quiz D) on Canvas.

- Complete pre-class case, Ms. Petrovich

- Prepare answers to discussion questions on pre-class cases (emailed when case opens on Canvas).

Learning Objectives

- Describe the use of thresholds to test and thresholds to treat

- List the common and life/function threatening causes of shortness of breath.

- Build a prioritized differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with shortness of breath that includes common and life/function threatening causes.

- Identify the components of the history and physical, as well as the laboratory and radiological findings, crucial for correctly diagnosing a patient presenting with shortness of breath

REVIEW OF THRESHOLDS TO TEST AND TREAT

The concepts of threshold to test and threshold to treat are two of the more difficult concepts in clinical reasoning as they can vary greatly from patient to patient and disease to disease. They are, however, crucial to understanding testing and treatment in individual patients. Below is a quick review followed by description of several common scenarios and how to use thresholds in sorting out the best diagnostic and treatment plans.

The threshold to test is a level of disease probability below which no further testing is necessary for that disease. In other words, the likelihood of disease is low enough that we no longer need to have it on the list of potential diagnoses. It is determined through considering the risks and benefits of testing versus not testing for the specific disorder. A low threshold to test is associated with:

-diseases associated with mortality or substantial morbidity (especially if there is an effective treatment), and

-tests for diseases that are accessible, low-risk, and effective at assessing the likelihood of disease.

An examples of a disease with a low threshold to test is pulmonary embolism (PE). Untreated PE poses a significant mortality risk (as high as 15%) and cannot be missed. D-dimer testing, as a blood test, is low risk and accessible, although its utility is limited in decreasing the likelihood of PE. CT angiogram of the chest is generally low risk (although there are certain populations where it can be higher risk such as young/pregnant patients or patients with advanced kidney disease). Therefore, in the case of a possible PE, our threshold to test would be very low. If PE were not a lethal disorder or if the only test available were, for example, an invasive pulmonary angiogram, the threshold to test would be higher.

The threshold to treat is the clinical probability of a disease above which treatment is thought reasonable. The threshold to treat is lower when the disease is associated with significant morbidity or mortality (i.e., we want patients to benefit from the therapy) but higher when the treatment is associated with significant risk or is of limited efficacy.

Pulmonary embolism is also a good example of these concepts. PE is associated with high mortality and morbidity, so we’d like to set the threshold to treat low, but the treatment (anticoagulation or thrombolytic therapy) is associated with a significant risk of bleeding, so the threshold to treat ends up being high.

Setting Thresholds

It is important to realize that thresholds are set BEFORE one does the testing for a specific disease. Doing so helps evaluate whether one should even do a particular test.

For example:

–If the probability of disease is below the threshold to test, no testing should be done and diagnostic efforts should focus on other diseases. For example, if the probability of acute cholecystitis is 2% and the threshold to test is 5%, a right upper quadrant ultrasound for the purposes of assessing the likelihood of acute cholecystitis should not be done. Diagnostic efforts should focus on the other diseases that make up the 95% of possibilities.

-If the probability of disease is above the threshold to treat, no testing is usually done and treatment should be started. Note that depending on the circumstances, testing may be indicated even after the threshold to treat has been exceeded (e.g., we may still obtain a chest film in patients in whom we are above the threshold to treat for pneumonia on the basis of the history, physical, and lab tests, partially because it can inform prognosis and treatment).

-If the probability of disease is between the threshold to test and the threshold to treat, then testing should be done. Each possible test should be looked at individually to see if the results of the tests (positive or negative) will result in a probability below the threshold to test or above the threshold to treat.

Diseases to consider in the initial evaluation of a patient with dyspnea

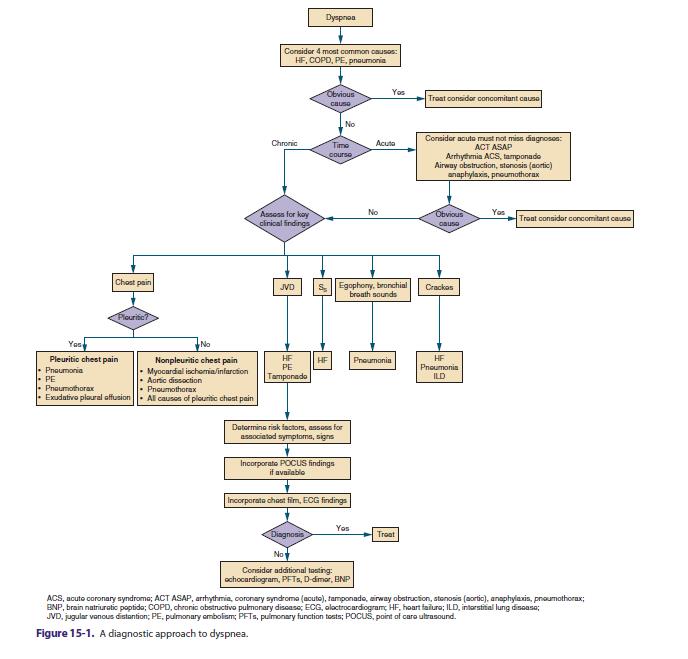

In building a differential diagnosis, it’s helpful to explicitly consider the common causes and the “can’t miss” diagnoses (those that pose an immediate threat to life or function). By memorizing the below four most common causes and knowing the ACTASAP mnemonic, we can rapidly direct our thinking and patient evaluation in an expeditious and efficient manner, which is very helpful when a patient is experiencing acute shortness of breath. There are many other causes of dyspnea we want to consider (e.g., lung cancer), but often rapid evaluation and treatment is necessary and using this structure helps us in accomplishing this.

| Four most common causes | Heart failure

Pneumonia Obstructive lung disease (COPD, asthma) Pulmonary embolism |

| Immediate threat to life

ACTASAP mnemonic |

Arrhythmia

Coronary syndrome Tamponade Airway obstruction Stenosis, Aortic Anaphylaxis Pneumothorax |

AN ALGORITHMIC APPROACH TO DYSPNEA

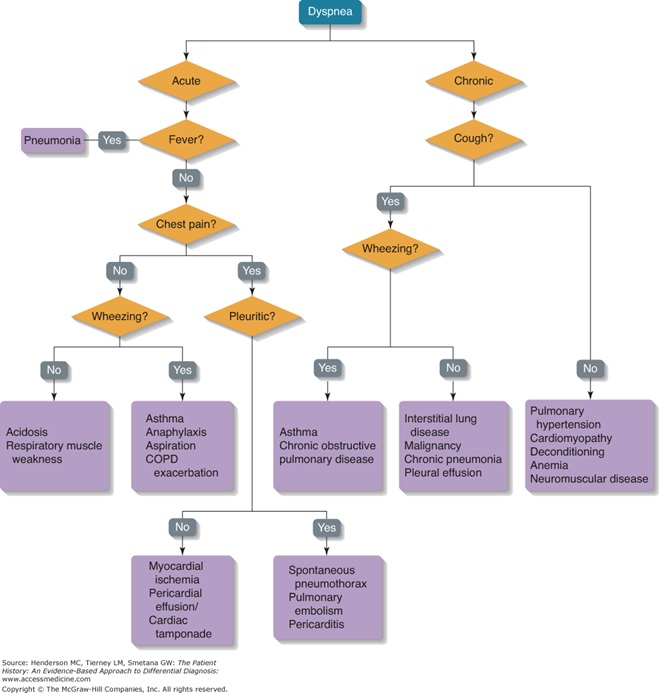

Algorithmic thinking involves a defined set of steps that help one arrive at a solution. The two diagrams below outline different algorithmic approaches to the differential diagnosis of dyspnea. They are meant for general guidance and should not be viewed as absolute (i.e. in the first algorithm, not all patients with acute dyspnea and fever have pneumonia).

RESOURCES FOR FURTHER READING

- Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine, “Dyspnea”

- UpToDate, “Approach to the patient with dyspnea”

- Academic Medicine, “Uses and Misuses of Thresholds in Diagnostic Decision Making”: http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com/sp-3.20.0b/ ovidweb.cgi?QS2=434f4e1a73d37e8cbc3152776b9fd7478bc68c745ba7591b11750a4581f6a9e0