9 Week 6: Chest Pain (Week of 5/15/2023)

Week 6: Chest pain

DISCUSSION SESSIONS Week of 5/15/23

Assignments Due: 5/16/2023 @8:00 AM

Prior to Class

- Read syllabus section on chest pain (below).

- Complete the required quiz (Quiz E) on Canvas.

- Complete pre- class case, Mr. Simpson.

- Prepare answers to discussion questions on pre-class cases (emailed when case opens on Canvas).

Learning Objectives

- Define heuristics and their role in clinical reasoning.

- Describe the availability and representativeness heuristic.

- List the six “can’t miss” diagnoses in a patient presenting with chest pain.

- Build a prioritized differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with chest pain that includes common and life/function threatening causes.

- Identify the key components of the history, physical exam, laboratory, and radiological studies for a patient with chest pain.

HEURISTICS

Hypothesis generation often occurs using heuristics, mental shortcuts, or rules of thumb (e.g., “if you see smoke, think fire”) that we use to make fast decisions based on pattern recognition. Importantly, although experienced clinicians utilize heuristics frequently, they often are unaware they are doing so. The use of heuristics is unconscious, although with metacognition (reflection on our thinking), clinicians may recognize that they have used one in retrospect.

Clinicians frequently use the availability heuristic, an unconscious mental shortcut in which particularly fresh, memorable, or common diagnoses come to mind when triggered by certain patient characteristics, clinical findings, or events. For example, if a patient presents with fever, cough, and myalgia during flu season, influenza immediately and unconsciously pops into our head on the basis of the availability heuristic as this is fresh and available in our minds. Similarly, if the first patient you saw as a medical student with acute kidney injury had a rare vasculitis, microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), you may try and diagnose every patient who presents with AKI with MPA because it was such a memorable case for you. When diseases are common, these heuristics make sense. In the above case of influenza, because the heuristic is associated with a common disease, you’ll be correct more often than not. However, if your availability heuristic for renal failure always tilts you toward MPA, a rare condition, then the heuristic is likely to worsen your diagnostic accuracy. Even in people with clinical features that are consistent with MPA, it is unlikely that they have the disease because of its exceedingly low prevalence.

Another commonly used mental short-cut is the representativeness heuristic: If it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, and walks like a duck, then it must be a duck. Clinicians use this heuristic when the presenting signs and symptoms are thought to be representative of a particular disease or diagnosis. Although often correct, the representativeness heuristic may cause error when either the presentation is atypical for the true diagnosis (e.g. stabbing chest pain in acute coronary syndrome) or when an alternate diagnosis masquerades as a common presentation of another diagnosis (e.g., esophageal spasm causing substernal pressure). Both of these scenarios occur commonly in clinical medicine. Keep in mind that diseases don’t always present the way in which they are described in textbooks (“diseases don’t read textbooks”). There is extraordinary variability in how a given disease may present from patient to patient.

Heuristics form much of the basis for pattern recognition. While heuristics are often correct, they are also a leading cause of diagnostic failure. The anchoring phenomenon is one such example. This refers to when we anchor on one aspect of the presentation or one diagnosis and do not consider other information or diagnoses. Frequently, we may skip over questions that are pertinent to the etiology of a presentation, because we think we’re on the right track in pursuing a hypothesis that may be incorrect. The failure to reassess a patient with the emergence of new data that contradicts the leading diagnostic hypothesis is called anchoring. Anchoring has its basis in the fact that it requires less mental exertion to hold onto your original diagnostic hypothesis than to develop a new one. Thus, new data that contradicts the original hypothesis is ignored or disregarded. You have set your anchor inflexibly on one hypothesis, and this creates diagnostic inertia. This can lead to premature closure, making a diagnosis without considering all the key data. Usually, this occurs because the physician recognizes a diagnostic pattern but fails to notice contradictory data or to verify their hypothesis using an analytic approach. When unexpected data appears, it is often necessary to retrace your steps and examine the history and physical in light of the new information.

For further information on heuristics, see the “Guide to Heuristics” section at the end of the syllabus.

WORST CASE SCENARIO MEDICINE

One very common method of analytic reasoning employed to generate hypotheses is worst-case scenario medicine. The clinician actively and consciously considers the worst possible diagnoses that could be causing a sign or symptom. For example, some clinicians will always try to rule out necrotizing fasciitis and deep venous thrombosis before settling on a diagnosis of cellulitis in a patient with a red leg. In the case of chest pain, the initial questioning of the patient may focus more on the “Serious Six” rather than on the other more common causes of chest pain. These six disorders may be treated effectively if they are diagnosed early in a patient’s course, but delays in diagnosis or treatment may result in patient death. There are many other disorders on the differential for chest pain that are serious, but these are the ones that a clinician must initially consider.

The serious six causes of chest pain include: acute coronary syndrome, pericarditis/tamponade, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, and esophageal rupture.

Use of Prediction Rules

Evaluating a patient with chest pain is another reminder of how epidemiological data help us in diagnosis. In the case of chest pain, we have robust epidemiological data that can provide a pre-test probability of CAD.

Probability of obstructive CAD on basis of age, sex and symptoms (Gulati et al JACC 2021)

| Age | Chest Pain* | Chest Pain* | Dyspnea | Dyspnea |

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| 30-39 | <=4 | <=5 | 0 | 3 |

| 40-49 | <=22 | <=10 | 12 | 3 |

| 50-59 | <=32 | <=13 | 20 | 9 |

| 60-69 | <=44 | <=16 | 27 | 14 |

| 70+ | <=52 | <=27 | 32 | 12 |

*Chest pain = refers to “cardiac” chest pain with symptoms “typical” of chest discomfort arising from coronary artery disease (e.g., retrosternal, building gradually in intensity, usually precipitate by stress – physical or emotional – with characteristic radiation). Probabilities of obstructive coronary artery disease will be lower for patients with forms of chest discomfort less commonly seen with CAD (previously referred to as “atypical” and now characterized as “possible cardiac” or “non-cardiac” chest discomfort).

Data such as these can be very helpful in estimating an initial pre-test probability. Two issues with utilizing such data, however, are: 1) our patients’ clinical presentations are often different from those of the patients in the studies, 2) not all diseases have these data available. Nonetheless, extrapolating the data can be very useful and provide a general estimate of the likelihood of a particular disorder.

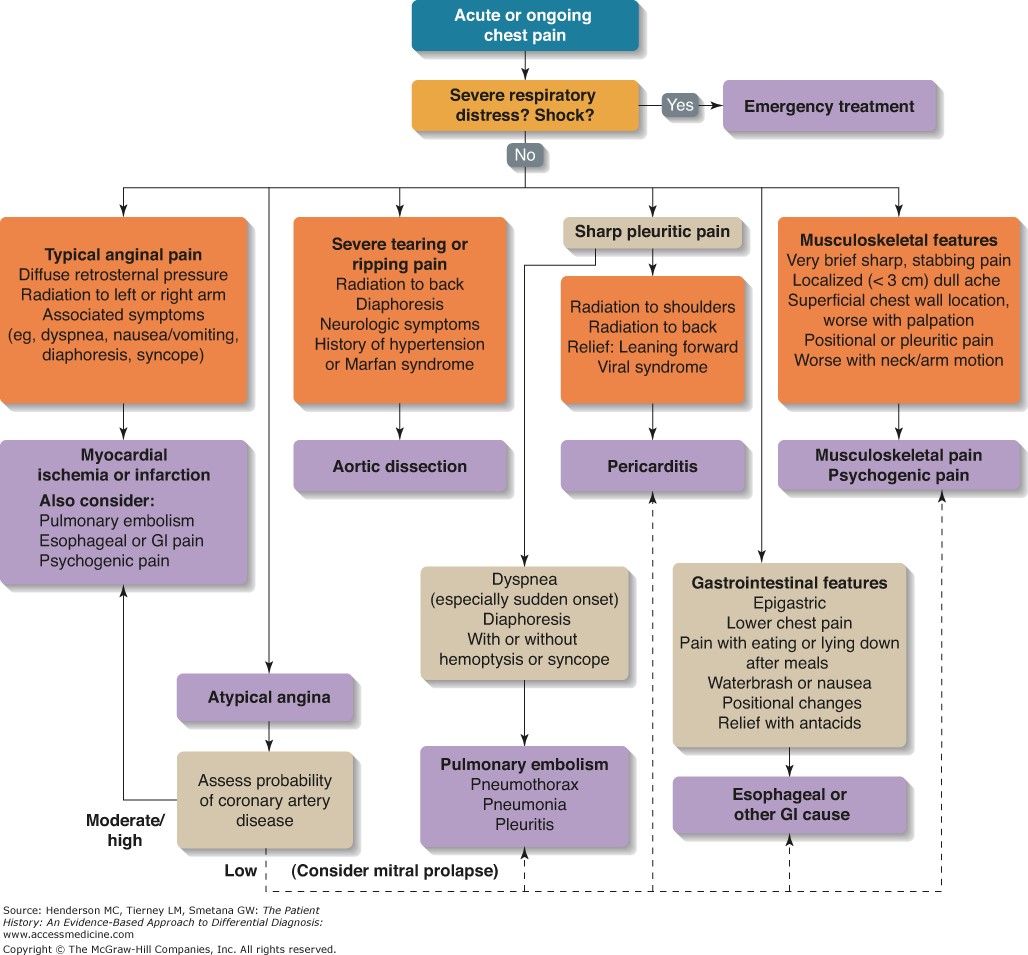

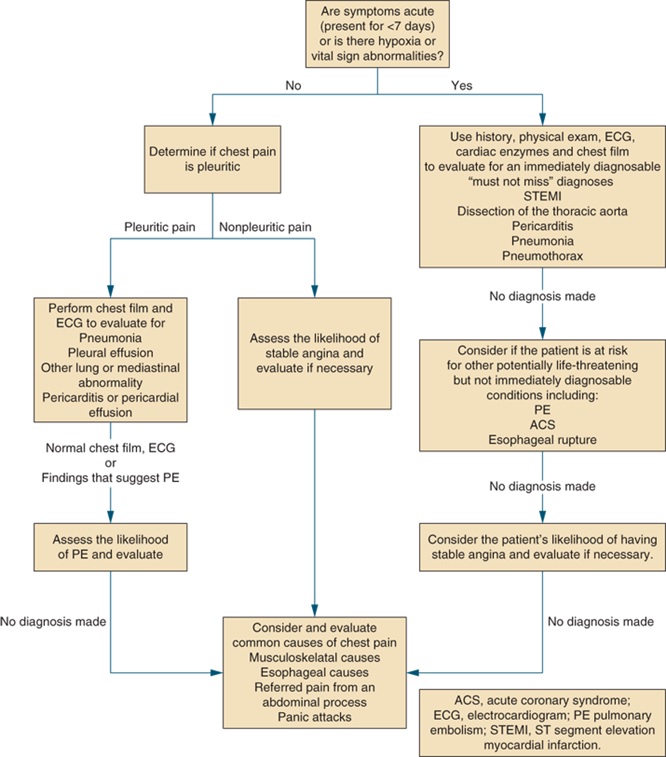

An Algorithmic Approach to Chest Pain

Resources for Further Reading

- Pathophysiology of Disease: An Introduction to Clinical Medicine, “Cardiovascular Disorders: Heart Disease”

- UpToDate, “Evaluation of the adult with chest pain in the emergency department”