16 Week 12: Diagnostic and Treatment Uncertainty (Week of 11/27/2023)

Week 14: Diagnostic and treatment uncertainty

DISCUSSION SESSIONS Week of 11/27/23

Assignments Due: 11/28/2023 @8AM

PRIOR TO CLASS

- Read the syllabus section below on uncertainty

- Complete the required quiz (Quiz K) on Canvas.

- Watch the “Uncertainty” video on Canvas.

- There is no pre-class case to complete

Learning Objectives

- List the underlying etiology of uncertainty

- Formulate a plan for managing uncertainty in clinical practice

- Apply techniques for managing and coping with uncertainty in the clinical setting

UNCERTAINTY IN MEDICINE

Although firmly rooted in science, uncertainty is ubiquitous in medicine. As much as we’d like to think that we’re usually able to establish a diagnosis with certainty, in truth there is almost always some degree of uncertainty in making a diagnosis. Remember that diagnosis is an exercise in categorization…we are trying to categorize a patient’s symptoms, signs, and laboratory/imaging findings such that we might be able to determine the best treatment and assign a prognosis. In doing so, we may over- or underemphasize some aspects of the presentation or unwittingly make an erroneous categorization. Think about our prior discussions about thresholds. We often say that the threshold to treat pulmonary embolism is about 80%…but inherent to this is the fact that some patients treated as having pulmonary embolism will in actuality not have one. Similarly, we may set the threshold to test for pulmonary embolism at 2%. Inherent to this is the fact that we will miss some pulmonary emboli despite having seemingly “ruled it out”. This is not because we have set the thresholds incorrectly, but rather there a great deal of uncertainty in all that we do in medicine. The ubiquity of uncertainty is not limited to diagnosis but extends to treatment as well. Despite years of study, it remains unclear as to the best means of treating (or not treating) low-grade prostate cancer. Similarly prognostication in medicine is fraught with tremendous uncertainty. The prevalence of uncertainty in medicine can be very frustrating and unnerving for both clinicians and patients. There are, however, techniques that can help us both embrace and deal with this uncertainty.

ETIOLOGY OF UNCERTAINTY

As with many things, if we understand the origins of uncertainty, we may be able to better deal with it. Some causes of uncertainty we may be able to mitigate while others we may just need to accept. Being able to recognize the difference is very important.

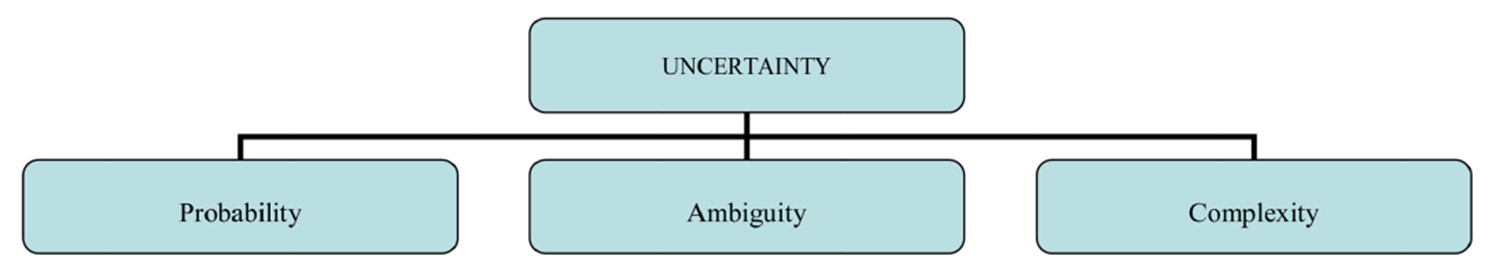

One conceptualization of the etiology of uncertainty is to think of the three main causes; risk/probability, ambiguity, and complexity.

Risk/Probability

Risk or probability causes uncertainty since there is the possibility that many different things can happen in any given situation. Think about a horse race. It may be likely that the favorite will win, but there’s also a probability that every other horse in the race could win. The vast majority of patients presenting to a primary care office with a headache do not have a brain tumor, but a brain tumor is in the differential. There’s always a chance. This uncertainty can be very difficult to deal with, especially when thinking about the possibility of a lethal diagnosis.

Ambiguity

Ambiguity as a cause of uncertainty arises from absent, unclear, or conflicting information or when things may be interpreted in many different ways. Absent information occurs when we don’t have good information on how to diagnose or treat a disease. As much evidence as we have, there are a lot of decisions that are based on “expert opinion” or lore without clear supporting information. Unclear information is also very common….one clinician sees an infiltrate on the chest film while another disagrees. Conflicting information is also very common. The white blood cell count may be elevated, indicative of a possible infection, but there may be no fever or other symptoms of an infection present.

Complexity

Medicine is VERY complex. We don’t have a great understanding as to why some patients with ACS have chest pain while others do not. We often don’t understand why some patients respond to a treatment while others do not. Although significant strides have been made in some areas of medicine (e.g., genetic testing and response to chemotherapy), we do not have similar information in most areas. Biology is very complex and an extraordinary number of variables come into play in trying to sort things out. Below is a graphic representation of the biochemical pathways in humans…extraordinarily complex: