1 Week 1: Abdominal Pain (Week of 2/27/2023)

Prior to Class

- Watch video lecture “Introduction to Clinical Reasoning”

- Read syllabus introduction.

- Read syllabus section on abdominal pain (below).

- Complete the pre-class case, Mr. Clark.

- Prepare an answer to the below discussion question based on the pre-class case (students may be called upon to give their answer):

- What are the key elements of the abdominal exam that help determine the cause of abdominal pain and severity of illness?

Learning Objectives

This week’s objectives are listed below:

- Create an accurate problem representation for a patient presenting with abdominal pain.

- Create detailed accurate illness scripts for common causes of abdominal pain.

- Practice comparing the patient’s problem representation to the illness scripts of the most likely diseases in order to determine a working diagnosis.

- List the serious six causes of abdominal pain.

- Build a prioritized differential diagnosis for a patient presenting with abdominal pain that includes the common and life/function threatening causes.

- Identify the key findings of the history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and radiological studies that are important for a patient with abdominal pain.

Creating an Accurate Problem Representation

To make a diagnosis (i.e., solve a diagnostic problem), clinicians must accurately define the problem that needs to be solved. In diagnosis, this means accurately determining the patient’s chief problem and using epidemiology, symptoms, signs, laboratory, and radiologic findings to properly contextualize the problem. The term used for this contextualized description of a patient’s problem or problems (i.e., chief concern) is called a problem representation. The better a clinician is able to represent a patient’s problem, the more likely they are to be able to find a disease that correctly matches it. This is similar to a Google search…. “Which terms are the best ones to use in a search to give me the information I need?” If one doesn’t represent the problem correctly by identifying the key aspects of a presentation, it is very difficult to come up with the correct diagnosis.

The problem representation should include the basic characteristics of the patient’s problem (i.e., qualifiers like location and character of pain) as well as semantic qualifiers, or adjectives, that clarify or specify the meaning of the chief concern.

Examples of semantic qualifiers include:

- Acute vs. subacute vs. chronic

- Mild vs. moderate vs. severe

- Intermittent (episodic) vs. persistent

- Stable vs. progressive

Creating an accurate and complete problem representation is a key step in making a diagnosis. For example, the differential diagnosis for chronic left lower quadrant abdominal pain is very different than that for acute right upper quadrant abdominal pain. By adding qualifiers, the differential diagnosis can be reduced from 100’s of possibilities to 10 or 20.

Another example of problem representation is the creation of a “key features” or “diagnostic considerations” list. Creating this list can help clinicians see patterns that may not have been obvious initially and can lead to a correct diagnosis. Key features lists, which are the problem representation written out in list form, include the following:

- Patient’s chief concern and basic characteristics of this problem

- Additional symptoms and signs (associated and non-associated)

- Key risk factors based on epidemiology (e.g., age, sex)

- Past medical history, family history, social history, and medications

This list is similar to but distinct from a patient’s problem list. This list will contain things like “older male” that are not problems in and of themselves, but that have a major impact on the diagnostic possibilities and differential diagnoses.

The Dual Process Model of Clinical Reasoning

Once clinicians form a problem representation, they compare it to the patterns of diseases in their memory. These mental constructs of diseases include epidemiology, history, physical examination, laboratory results, and imaging findings and are called illness scripts. Illness scripts are largely unconscious and are formed from dedicated study and prior clinical experiences. The more experienced a clinician is, the more complete, nuanced, and complex their illness scripts are. Clinicians thus compare and contrast the problem representation they’ve constructed with their various illness scripts until they find the best match. This process of “script selection” is the basis for diagnostic reasoning.

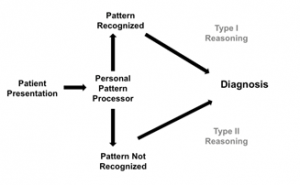

Clinicians use two basic types of reasoning in script selection, specifically non-analytic reasoning (i.e., Type I reasoning, pattern recognition, intuitive reasoning, “a gut feeling”) and analytic reasoning (i.e., Type II reasoning). Non-analytic reasoning (which we’ll call pattern recognition) is the fundamental way that we solve problems, not just in clinical reasoning, but also in our everyday lives. This is sometimes called the Aunt Millie method. It gets its name from the quip, “How do I know this person is Aunt Millie? Because it’s Aunt Millie!”. Essentially, this name emphasizes a decision-making strategy that relies on the recognition of a pattern; in the case of Aunt Mille, the pattern is all of her characteristics. We don’t need to think about who the person is as it’s obvious to us that it’s Aunt Millie. Pattern recognition is highly efficient, requires little effort, and often accurate.

Analytic reasoning is a more deliberate approach to a problem. It involves consciously thinking through a problem using one of many approaches or techniques. Analytic reasoning is slower, more effortful, and requires knowledge of the technique. Examples of analytical reasoning include hypothetico-deductive reasoning, probabilistic reasoning, algorithmic thinking, and worst case scenario medicine. Hypothetico-deductive reasoning is a process of reasoning that starts with a hypothesis and then seeks to find evidence that increases or decreases its probability. If that hypothesis is refuted, then a new hypothesis is generated and the process is repeated. Probabilistic reasoning involves considering the probability of disease based on its incidence and algorithmic thinking involves arriving at a solution via a clear and defined set of steps. Worst case scenario medicine involves consciously considering the most serious diagnoses for a specific patient presentation.

The combination of pattern recognition and analytical reasoning is known as the dual process model of reasoning. Clinicians constantly bounce between pattern recognition and analytic reasoning as the two processes are complementary and serve to check each other. Both processes are sometimes faulty, leading to diagnostic failure either as the primary thought process or by erroneously over-riding a previously correct diagnosis arrived at by the other system. The most expert clinicians rely heavily on pattern recognition, but then know when to “check their work” using analytical reasoning. Less experienced clinicians are often more dependent on analytical reasoning as they don’t have the illness scripts to rely on pattern recognition. Most clinicians (and people) prefer pattern recognition as it’s so fast and effortless, but avoiding the cognitive miser effect is an important part of being a good clinician.

| Table 1. Basic Characteristics of the Two Types of Clinical Thought | ||

| Pattern Recognition (Type I) | Analytical Reasoning (Type II) | |

| SPEED | Fast | Slow |

| AWARENESS | Unconscious | Conscious |

| EFFORT | Low | High |

| RELIABILITY | It depends* | High |

| ERROR LIKELIHOOD | Variable | Variable** |

| * Type I reasoning has a high level of reliability for experts in routine cases and a low-level reliability for non- experts in complex cases. In rare or complicated cases, combining the two types of clinical thought improves accuracy. | ||

| ** Cognitive overload can compromise the accuracy of Type II reasoning. Working memory can handle no more than about 7 (±2, depending on the person) pieces of information at a time. Considering a high volume of data at once can cause the brain to become less effective in processing and increases the likelihood of error. | ||

The Process of Diagnosis

Diagnosis is a form of (often unconscious) categorization. This is not just a practice that physicians utilize; everyone uses it in daily life. For example, “dog” is associated with a set of characteristics that allow us to recognize a dog we’ve never seen before as a dog. In the same way, “heart failure” is associated with a set of signs and symptoms that an experienced clinician can recognize, even if they are seeing a new patient. This is reflected in the below figure where one’s “personal pattern processor” (i.e., their brain with its illness scripts) either recognizes a pattern and comes to a diagnosis via pattern recognition or doesn’t recognize a pattern and thus needs to use an analytical technique to come to a diagnosis.

A pattern may not be recognized in a clinical setting due to a number of factors beyond clinical inexperience. The rareness of a disorder, atypical presentations, unrelated confounding findings, and the presence of more than one disease can all confuse the process. In these instances, analytic reasoning techniques are very useful.

The process of diagnosis is more iterative than depicted above and includes an (often unconscious) cycle of hypothesis generation and hypothesis refinement. Clinicians often first generate a hypothesis based on pattern recognition. For example, as soon as one hears the patient is a 62-year-old male with chest pain, one thinks of acute coronary syndrome (i.e., generates ACS as a hypothesis). Once a hypothesis is generated, one seeks out data to test the likelihood of the hypothesis being true through the patient history, exam, and test results. In going through this process using both pattern recognition and analytical reasoning, hypotheses are refined, some are discarded, new ones are generated, and eventually a working diagnosis is established.

This is a fluid process and occurs rapidly in real-time. A clinician usually changes their diagnostic thinking multiple times throughout the process as more information is obtained. It is like working through a maze in which they take several routes that initially make sense, but eventually lead to dead ends, forcing reconsideration of the direction taken.

For example, a patient may come in with episodic right upper quadrant abdominal pain making one estimate biliary colic as very likely. Upon examining the patient, however, a surgical scar is seen in the right upper quadrant and it comes out that the patient’s gallbladder was previously removed surgically. This causes the probability of biliary colic to be reduced to near zero and forces consideration of other causes of right upper quadrant pain.

The situation described above highlights two other important concepts, the competing hypothesis effect and the corollary effect. The probabilities of the diagnoses on the differential diagnosis must add up to 100%. Adding or deleting diagnoses to the list must result in a change in the probabilities of the other diagnoses on the list. The competing hypothesis effect occurs when the addition of new hypothesis automatically lowers the probability of at least one other hypothesis on the differential diagnosis list. The corollary effect occurs when the removal of a hypothesis automatically increases the probability of at least one other hypothesis on the differential diagnosis list.

Approach to Abdominal Pain

Abdominal pain is a challenging chief concern. The causes range from benign to life-threatening and patients frequently present with atypical symptoms and signs. Diagnostic errors, such as premature closure (see “Guide to Heuristics” at the end of the syllabus) are common, and building a good differential diagnosis is critical. A good way of building a complete differential for abdominal pain is to apply potential causes of disease using the mnemonic VINDICATE (see glossary) to each of the structures (e.g., liver, gallbladder, small bowel, etc.) within the abdomen. The quadrant approach described below can help further delineate the differential.

The use of imaging, especially CT scans, is common early in the diagnostic process given how challenging finding the exact cause of abdominal pain can be. However, evidence demonstrating improved patient outcomes by using this strategy has not been clearly established. The harms of excessive imaging include discovery of findings that have no clinical import (i.e., “incidentalomas”), increased cancer risk due to radiation exposure, high cost, and erosion of clinical skills.

The best approach is a balanced one that combines a directed history and physical with a thoughtful approach to diagnostic testing. Eliciting the location of pain and acuity of onset, along with performing a thorough but directed exam, are all critical in distinguishing causes of abdominal pain.

In determining the location of the pain, it is useful to separate the abdomen into four quadrants using the umbilicus as a landmark. By placing one’s hand horizontally across the umbilicus and asking the patient if it hurts more above or below the hand, one can distinguish between upper and lower abdominal pain. By then placing the hand vertically over the umbilicus and asking whether it hurts more to the right or left, one can establish laterality of the pain. This basic approach is a good means of specifically locating the pain, which is important as many diagnoses characteristically occupy one or more abdominal quadrants.

The Table below lists many of the important causes of pain separated by quadrant and will help to begin building a differential based on the location of pain. It is also imperative keep in mind the “Serious Six” causes of abdominal pain that pose an immediate risk to life. The first four are associated with vascular disease, whereas the last two are associated with peritonitis. Several of these can present with diffuse abdominal pain.

- Acute mesenteric ischemia

- Leaking/ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Aortic dissection

- Inferior myocardial infarction

- Acute intra-abdominal infection with peritonitis

- Viscous rupture with peritonitis

Additionally, two general statements can be made regarding acuity as it relates to abdominal pain. Firstly, inflammatory causes of abdominal pain, such as, appendicitis, cholecystitis, pyelonephritis, and diverticulitis, initially cause more mild pain, which then progresses. Secondly, intense abdominal pain that comes on suddenly suggests obstruction, perforation, or ischemia as the etiology, such as mesenteric ischemia, renal colic, biliary colic, and bowel perforation.

| Table 1. Abdominal pain diagnostic grid. | |

| Right upper quadrant | Left upper quadrant |

| Chest (AMI, PE, basilar pneumonia)

Peptic ulcer disease Pancreatitis Hepatitis Biliary colic Cholecystitis, cholangitis Incarcerated ventral hernia Small/Large bowel obstruction Right kidney (stone, infarct, infection) Mesenteric ischemia

|

Chest (MI, PE, basilar pneumonia)

Peptic ulcer disease Pancreatitis Spleen (rupture, abscess, infarct) Incarcerated ventral hernia Small/Large bowel obstruction Diverticulitis (more typically LLQ) Left kidney (stone, infarct, infection) Mesenteric ischemia Leaking AAA Sigmoid volvulus |

| Right lower quadrant | Left lower quadrant |

| Right gonad (cyst, torsion, infection)

Ectopic pregnancy Right inguinal hernia Small/Large bowel obstruction Diverticulitis (usually LLQ) Mesenteric ischemia Leaking AAA (less likely) Appendicitis Cecal volvulus |

Left gonad (cyst, torsion, infection)

Ectopic pregnancy Left inguinal hernia Small/Large bowel obstruction Diverticulitis Mesenteric ischemia Leaking AAA Appendicitis (less likely) Sigmoid volvulus |

|

Generalized pain Any cause associated with perforation or rupture (e.g., perforated appendicitis) Mesenteric ischemia AAA Bowel obstruction |

|

|

Table 2. Common Causes of Abdominal Pain. Adapted from: Symptom to Diagnosis: An Evidence- Based Guide |

||||||

| Location | Differential Diagnosis | Time Course | Cause of concomitant hypotension (if present) | Clinical Clues | ||

|

Right upper quadrant |

Acute | Chronic | ||||

| Hyperacute | Acute | |||||

| Biliary disease | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Sepsis | Postprandial pain, jaundice | |

| Hepatitis | ✓ | Alcohol use, IV drug use, jaundice | ||||

| Pancreatitis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hypovolemia | Alcohol use, gallstones | |

| Renal colic (flank pain) | ✓ | ✓ | Hematuria (usually microscopic), severe pain | |||

| Left upper quadrant | Renal colic (flank pain) | ✓ | ✓ | Hematuria (usually microscopic), severe pain | ||

| Splenic infarct or rupture | ✓ | Hemorrhage | Endocarditis, trauma, shoulder pain | |||

| Epigastrium | Biliary disease | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Sepsis | Postprandial pain, jaundice |

| Pancreatitis | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Sepsis | Alcohol use, gallstones | |

| Peptic ulcer | ✓ | ✓ | Hemorrhage | Melena, hx of NSAID use | ||

| Diffuse periumbilical | AAA | ✓ | Hemorrhage | Smoking, male gender, hypotension, syncope, pulsatile abdominal mass | ||

| Appendicitis | ✓ | ✓ | Sepsis | Migration and progression of pain | ||

| Acute mesenteric ischemia | ✓ | Sepsis | Hx of AF, heart failure, valvular heart disease, catheterization, pain out of proportion to exam | |||

| Bowel obstruction | ✓ | Sepsis, hypovolemia | Inability to pass stool or flatus, prior surgery | |||

| Chronic mesenteric ischemia | ✓ | PVD or CVD,

pain brought on by food, weight loss |

||||

| Gastroenteritis | ✓ | Hypovolemia | Diarrhea, travel history | |||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Sepsis, hypovolemia |

Family history, hematochezia, weight loss | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | ✓ | Intermittent diarrhea or constipation | ||||

| Splenic rupture | ✓ | Hemorrhage | Trauma | |||

|

Right lower quadrant |

Appendicitis | Sepsis | Migration and progression | |||

| Ectopic pregnancy | ✓ | Hemorrhage | Sexually active woman in child bearing years | |||

| Ovarian torsion | ✓ | |||||

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | ✓ | ✓ | Sepsis | Sexually active woman, vaginal discharge, cervical motion tenderness | ||

| Lower left quadrant | Diverticulitis | ✓ | ✓ | Sepsis | ||

| Ectopic pregnancy | ✓ | Hemorrhage | ||||

| Ovarian torsion | ✓ | |||||

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | ✓ | ✓ | Sepsis | |||

| AAA = abdominal aortic aneurysm, AF = atrial fibrillation CVD = cardiovascular disease, NSAIDs = non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, PVD = peripheral vascular disease | ||||||

Resources for Further Reading

- Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine: “Abdominal Pain”

- UpToDate: “Evaluation of the adult with abdominal pain”

- From Symptom to Diagnosis: “Abdominal Pain”