Assignments

Assignments Checklist

All assignments should be submitted to Michelle Freitas by 8:30am on the due date unless otherwise noted.

| Assignment | Due Date | Calendar Date |

| Info Mastery Topic | Monday of Week 4 (email to Dr. Cyr) | 2/17/2020 |

| PACT Table | Thursday of week 6 (email to freitm@mmc.org/in person) | 3/5/2020 |

| Info Mastery Presentation | Friday of week 6 (presented in person) | 3/6/2020 |

| Mid-Clerkship Evaluation | Email to Michelle by the end of the 4th week (freitm@mmc.org) (make sure preceptor has signed the eval). | 2/21/2020 |

| 3 DOC Cards (1 Pain + 2 more) | Thursday of week six (email freitm@mmc.org/in person) | 3/5/2020 |

| 5 Wishes Reflection | Thursday of week 6 (email freitm@mmc.org) | 3/5/2020 |

| Home Visit | Thursday of week 6 (email freitm@mmc.org) | 3/5/2020 |

| 16 FM Cases | DD5 (@ aquifer.org) | 3/2/2020 |

| >75 Patient Logs | DD5 (TUSK) | |

| Extra Credit | Thursday of week 6 (email freitm@mmc.org) | 3/5/2020 |

Patient-Centered Cross Cultural Communication Exercise

PACT (short Kleinman* model): Problem, Affect, Concern, Treatment

Problem: Asks for the patient’s perspective on the problem. For example:

–What do you think is causing the problem?

–What do you think contributed to the problem or brought it on?

Affect: Asks how the problem is affecting the patient’s life. For example:

–How is this problem affecting the rest of your life?

–Has your work or home life been affected by this problem?

Concern: Asks what the patient’s greatest concern is. For example:

–What worries you the most about this problem?

–What are you most concerned about today?

Treatment: Asks if the plan is acceptable to the patient. For example:

–Do you feel comfortable with this treatment plan?

–Do you see any barriers that might prevent you from follow this plan?

Caring for diverse patients in a patient-centered and culturally appropriate way is an essential skill for all physicians. You will practice using these advanced communication questions to help elicit the patient’s perspective during the Family Medicine Clerkship with at least 3 patients. One patient should have an acute or chronic pain concern. These questions can help improve communication with all patients, regardless of their cultural background. The patients you practice using these questions with do not need to be from a cultural or ethnic group different from your own. However, these questions have been found to improve communication in a cross-cultural setting as well. A summary of cultural competency topics is in the clerkship materials for your review.

Complete this assignment prior to Didactic Day 3, when we will be practicing advanced communication with standardized patients.

Grading:

This assignment must be done during the Family Medicine Clerkship. Students who do not complete the PACT assignment prior to Didactic Day 3 will lose 5 points from their final grade.

*Kleinman, Arthur, Leon Eisenberg, and Byron Good. 1978. “Culture, Illness, and Care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research”. Annals of Internal Medicine 88:251-258.

Patient-Centered Advanced Communication Assignment

Due by the 6th Thursday of the block

| Patient # | Patient’s Initials | Patient’s Medical Problem or Diagnosis |

| 1. | **Acute or Chronic Pain** | |

| 2. | ||

| 3. |

Reflective Writing

Write a brief reflection about your experience using the PACT questions.

- What did you learn about your patient’s perspective?

- How did this information impact your diagnosis, workup or treatment plan, or overall patient care?

Cultural Competency and Health Disparities in Clinical Medicine

Cultural Competency

–The ability to communicate effectively with patients from diverse cultural, ethnic, religious, socioeconomic, and personal backgrounds with the goal of delivering high quality, effective, and mutually acceptable health care.

–“Providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.” – Institute of Medicine’s definition of patient-centered care.

Why Is It Important?

— Well documented health disparities show that certain patient populations (minorities, limited English speakers, lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgendered, elderly, disabled) receive poorer health care and have worse health outcomes.

— Up to 50% of the US population is projected to be comprised of “minority” groups as of 2050. The numbers of elderly and disabled patients continue to increase. Many “minority” patients (such as LGBT) cannot be visually identified.

— Personal health beliefs of each patient (which can be the result of culture, socioeconomic status, education level, religious beliefs, or personal experiences) factor into how a patient experiences illness, what treatments are acceptable to that patient, and what outcome is desired by the patient.

— Physicians who possess culturally competent attitudes, skills, and knowledge have been shown to provide better health care to patients, leading to better health outcomes and reduced health disparities.

Culturally Competent Attitudes

— Recognize what our own personal beliefs are about proper behavior, proper relationships, and proper health care decisions.

— Acknowledge that our patients often have different beliefs about proper behavior, relationships, and health care than we do.

— Realize that our own attitudes, overt beliefs, and unconscious biases affect how we care for our patients and can contribute to health disparities.

— Attempt to cultivate an attitude of cultural humility, where we are open to our patient’s beliefs, try to understand our patient’s perspective and individuality, and are accepting of who our patient is.

Culturally Competent Skills

— Patient-centered communication skills are highly effective at eliciting personal health beliefs that may affect patient care. Patient-centered care is culturally competent care.

— Patient-centered communication models such as the PACT questions, LEARN, ETHNIC, or BATHE models can help physicians remember to ask about the patient’s beliefs and perspectives.

— The skill of effectively working with a professional medical interpreter, and requesting an interpreter when appropriate, is vitally important to caring for patients with limited English proficiency.

— The skill of negotiating a mutually acceptable management or treatment plan is essential for effective care, and improves patient adherence, patient satisfaction, and patient health outcomes.

— Utilizing community or institutional resources to assist and support your patient can greatly improve a patient’s health experience, comfort, and health outcomes.

Culturally Competent Knowledge

— Knowing how and where to access resources to better care for diverse patients. Resources can be online, community-based, or part of your health care system or institution. Compiling a list of what the available resources are and how they might be used to assist patients in your specific location can increase use of these resources to the benefit of your patient.

— Use your clinical practice data in your electronic health record to evaluate what patients are due for preventive care and chronic health condition management, according to evidence-based medicine guidelines. Generate data by subgroups such as age, gender, ethnicity, language other than English spoken at home, etc. See if there are subgroups of your patients that are receiving sub-optimal care, and develop a plan to improve that. When a doctor is given data showing that her female elderly patients are 40% more likely to have poorly controlled hypertension compared to her male elderly patients, that doctor will likely make changes to her practice, or find innovative ways to better manage those patients. Individual patients may choose care (after informed consent) that is sub-optimal according to evidence-based guidelines, but is personally optimal for them. However, if an entire sub-group of patients has significantly poorer health quality markers or preventive care rates within a practice, there may be a need for physician awareness, patient education, group visits, and/or collaboration with local community organizations to improve health for this sub-group.

Useful Web Resources:

www.ethnomed.org

Information about cultural and ethnic groups in the US. Includes cultural profiles, clinical topics, bilingual patient education materials, and issues about cultural health beliefs.

http://spiral.tufts.edu

Selected Patient Information Resources in Asian Languages: Patient information handouts in English as well as multiple Asian languages about various health conditions.

http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/

Office of Minority Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Information about health disparities within the U.S., including programs to reduce disparities among minority populations. Also, cultural competency online CME and resources for clinicians at http://thinkculturalhealth.org.

Amy L. Lee, MD, FAAFP

Last Updated March 18, 2017

Information Mastery Exercise

The goal of this exercise is to practice identifying and answering clinical questions that arise in clinical medicine. You will first formulate an answerable question, and then use the synthesized or “secondary” medical literature to answer this question in a way that generates a useful solution to improve the health of the patient.

Step 1. Identify a clinical question.The question can concern a treatment or a diagnosis.

Step 2. Convert this question to a searchable question by using the PICO format:

Patient, Population or Problem

What are the characteristics of the patient or population? What is the condition/disease of interest?

Intervention

What do you want to do with this patient (e.g. treat, diagnose, observe)?

Comparison

What is the alternative to the intervention (e.g. different drug, surgery)?

Outcome

What are the relevant outcomes (e.g. morbidity (symptoms), mortality (death), or quality of life)?

For PICO help, see: learntech.physiol.ox.ac.uk/cochrane_tutorial/cochlibd0e187.php

Step 3. Select one or more of the following resources to find the answer:

DynaMed

Essential Evidence Plus

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

TRIP Database

Links to these resources are on the Databases page of the TUSM Hirsh Library.

Step 4. From the information found, determine the best answer to your clinical question.

Step 5. Identify the level of evidence or strength of recommendation.

Step 6. Apply the answer to the original patient situation.

Using your analysis, develop a PowerPoint talk (10 minutes) with the following slides:

1. The original clinical question

2. The PICO question

3. The method you used to search the resources (e.g., “I started with Cochrane and then checked Dynamed”)

4. The information you found

5. An analysis of this information, and the corresponding Level of Evidence or Strength of Recommendation

6. How you would apply the information to your patient situation

Guidelines for Evaluating Information Mastery Project

Mid-Clerkship Evaluation and Action Plan

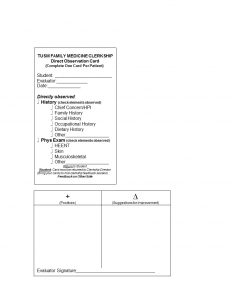

Direct Observation Cards (DOC)

You will need to submit 1 PAIN card and 2 DOC cards. For the non-pain DOC card, you only need to have one box checked. Your preceptor should give you written feedback on the back of the card. Write your name legibly. Due by DD5.

5 Wishes Reflection Assignment

After completing the Five Wishes booklet, please complete the following two-paragraph assignment.

In the first paragraph, describe how completing Five Wishes changes the way you think about end-of-life care. Identify which part of Five Wishes was the most difficult, what made it difficult, and how you got past the difficulty.

In a second paragraph, explain how going through Five Wishes will change the way you practice medicine in the future.

For further reading, visit the Aging With Dignity website.

The Home Visit Project

During the first 2 weeks of the clerkship, ask your preceptor to help you identify a patient appropriate for a home visit. Ideally, this will be someone you see in the office. Limit your home visit candidates to people over 65 or those with chronic disabilities whose conditions are significantly influenced by their home environment (e.g., could be a child with diabetes or persistent asthma).

Once your preceptor has obtained permission from the patient, you are responsible for organizing the entire visit. Contact the patient at home and schedule a mutually convenient time to meet. Try to arrange the visit when family members or other caregivers are present. Plan to stay for 1-2 hours. It is preferable that you do this visit on your own; however if safety is an issue you may go with your preceptor. Please see Home Visit Safety Policy at the end of these instructions.

The following is a guide to help you organize the information to gather at the time of your visit. Not all of the information will apply to every patient. Remember: The purpose of the home visit is to gather data that you would not be able to obtain during an office visit.

Medical history

- Active and inactive problems

- Direct observation of medications and medical equipment

- Preventive services

Nutritional history

- Appetite, typical food intake, availability and preparation of food

- Supplements, special diets

Social history

- COMPLETE THIS TOOL: “ACCOUNTABLE HEALTH COMMUNITIES CORE HEALTH-RELATED SOCIAL NEEDS SCREENING QUESTIONS”

- Observation of living environment. (Emphasize this history; it is why you are there.)

- Vocation and education

- Habits and lifestyle

- Community and in-home professional services

- Family support and social network

- Resilience: capacity to adapt to adversity

Functional evaluation

- Observation of Activities of Daily Living (ADL’s)

- Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL’s)

Physical examination

- General appearance, vital signs, mobility

- Montreal Cognitive Assessment [MoCA] (mocatest.org)

- Other aspects of exam as appropriate to setting (complete PE not required)

Complete the Home Visit worksheet on TUSK (Click Clinical Years → Family Medicine → Home Visit Worksheet). Feel free to use a brief, bulleted format for the worksheet or any format you wish. Your write-up should be not more than 2-3 pages.

Please discuss your findings with your preceptor and give a copy of the worksheet to him/her. Then email the completed worksheet. You will lose 5 points on your overall grade if you do not submit your worksheet prior to this deadline. Remember, the problem list should contain a combination of clinical and social issues. Focus on findings you discovered especially because you were at the patient’s home.

Home Visit Safety Policy

Purpose

The purpose of this policy is to minimize any potential risk to students while on home visits, and to establish uniform safety procedures for students engaged in home visits.

Background

Third year medical students taking the Family Medicine Clerkship are required to perform a home visit on a continuity patient from their preceptor’s office. There is essential educational value to the home-based evaluation and case report that cannot be re-created in the office setting. The importance of this curricular component is reflected in the ACGME residency requirement that residents must perform home visits.

Because there may be inherent risk in seeing a patient outside of the usual clinical setting (hospital or office), this policy is designed to make reasonable efforts to limit the level of risk.

Procedures

- Safety issues will be discussed in the orientation curriculum.

- Because risk and safety continuously vary, and geography does not solely predict safety, “universal safety precautions” should apply at all times.

- This policy and safety guidelines will be distributed to all preceptors in the Family Medicine Clerkship, and will be a part of the student and preceptor manuals.

- A student going on a home visit should let his or her preceptor or a designated member of the office staff know when the home visit will take place, and to which patient.

- If a student feels uncomfortable in a home visit situation, he or she should leave.

- In consultation with the primary preceptor, students should select a home visit patient based on educational needs, continuity, logistics, and potential safety issues.

- If a student feels that a home visit to a certain patient would be unsafe, he or she should discuss this with the preceptor. If the student cannot resolve this issue with the preceptor, the student should contact the clerkship director, who will work with the student and preceptor to identify an acceptable alternative to visiting that patient.

General Safety Guidelines

- Schedule all home visits in the morning or early afternoon.

- Always let someone in the office know your home visit schedule.

- Before leaving for a home visit, plan a route that allows for travel on major roads. Even if they are shortcuts, avoid dark, deserted places, secluded alleys, vacant lots, and parks.

- Dress in a professional manner. Do not wear expensive watches or jewelry.

- Carry only limited cash and credit cards.

- Wear your TUSM/MMC picture Identification. There is some evidence that a medical badge provides a certain amount of “safe passage.”

- Do not accept or give rides to strangers and/or patients and families.

- Walk on the sidewalk as close to the curb as possible, and against traffic to better able to see oncoming activity. Observe windows and doorways for loiterers.

- Do not enter the area if there is unrest in the neighborhood.

- Avoid lingering outside of buildings, especially in isolated areas.

- Be alert, develop an awareness regarding your immediate environment, and convey confidence and a sense that you know where you are going.

- Never give your name, home address, or telephone number to strangers.

- Yell “FIRE” instead of “HELP” and scream if in an uncomfortable situation.

- Do not enter a home if you feel uncomfortable.

- Use of pepper or chemical sprays is discouraged. They provide a false sense of security, are usually difficult to access when needed, and have a limited shelf life.

- If you are visiting an elevator building:

- Get on the elevator and stand close to the buttons. Locate the alarm button and push if necessary.

- Look into the elevator before entering.

- Do not enter the elevator if there is no light.

Guidelines Related to Transportation

- Keep your car in good working condition. Have enough gas for the day.

- Lock car doors and windows.

- Do not leave items of value or perceived value visible in your car.

- Do not park in an isolated area or where groups of people are loitering.

- Know where gas stations are.

- If you are taking public transportation, sit near a door. While not the best location in terms of theft, it is the best location in terms of personal safety.

Accountable Health Communities

Core Health-Related Social Needs Screening Questions

Underlined answer options indicate positive responses for the associated health-related social need. A value greater than 10 when the numerical values for answers to questions 7-10 are summed indicates a positive screen for interpersonal safety.

Housing Instability

1. What is your housing situation today?

◊ I do not have housing (I am staying with others, in a hotel, in a shelter, living outside on the street, on a beach, in a car, abandoned building, bus or train station, or in a park).

◊ I have housing today, but I am worried about losing housing in the future.

◊ I have housing.

2. Think about the place you live. Do you have problems with any of the following? (check all that apply)

◊ Bug infestation

◊ Mold

◊ Lead paint or pipes

◊ Inadequate heat

◊ Oven or stove not working

◊ No or not working smoke detectors

◊ Water leaks

◊ None of the above

Food Insecurity

3. Within the past 12 months, you worried that your food would run out before you got money to get more.

◊ Often true

◊ Sometimes true

◊ Never true

4. Within the past 12 months, the food you bought just didn’t last and you didn’t have money to get more.

◊ Often true

◊ Sometimes true

◊ Never true

Transportation Needs

5. In the past 12 months, has lack of transportation kept you from medical appointments, meetings, work or from getting things needed for daily living? (Check all that apply)

◊ Yes, it has kept me from medical appointments or getting medications.

◊ Yes, it has kept me from non-medical meetings, appointments, work, or getting things that I need.

◊ No.

Utility Needs

6. In the past 12 months has the electric, gas, oil, or water company threatened to shut off services in your home?

◊ Yes

◊ No

◊ Already shut off

Interpersonal Safety

7. How often does anyone, including family, physically hurt you?

◊ Never (1)

◊ Rarely (2)

◊ Sometimes (3)

◊ Fairly often (4)

◊ Frequently (5)

8. How often does anyone, including family, insult or talk down to you?

◊ Never (1)

◊ Rarely (2)

◊ Sometimes (3)

◊ Fairly often (4)

◊ Frequently (5)

9. How often does anyone, including family, threaten you with harm?

◊ Never (1)

◊ Rarely (2)

◊ Sometimes (3)

◊ Fairly often (4)

◊ Frequently (5)

10. How often does anyone, including family, scream or curse at you?

◊ Never (1)

◊ Rarely (2)

◊ Sometimes (3)

◊ Fairly often (4)

◊ Frequently (5)

fmCASES

Log into aquifer.org and complete 16 fmCASES, of which 8 are the cases listed below, and 8 are any cases of your choice. No additional submission is required.

Required Cases: #7, 9, 12, 18, 19, 27, 28, 33, plus eight more of your choice.

You will not get credit for any case completed on a prior clerkship. If one of the 8 required cases has already been completed on a prior clerkship, complete any other case of your choosing.

We highly recommend you start these cases early in the clerkship.

Extra Credit Opportunity (Optional)

As we wrap up the Family Medicine clerkship during this final week, take a minute to think about what you have learned over the past 6 weeks.

Make a list of your top 5 family medicine take home points — the things that you will take with you going forward. One or two sentences for each should suffice.

Your take home points may be used for clerkship improvement or research about clerkship education, but will not be connected with your name in any way. If you prefer that your points not be used for research, please indicate that on your submission.

Reasonable completion will earn you 1 extra credit point (1% of total final grade).