16 Introduction to Underserved Medicine

Introduction to Underserved Medicine – Preble Street Learning Collaborative

Learning Objectives

- Define and list examples of social determinants of health

- Describe the role of community health centers

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH (SDH):

- Economic and social conditions that result in differences in health status apart from genetic and individual biologic factors

- o WHO defines SDH in the following way:

- “The poor health of the poor, the social gradient in health within countries, and the marked health inequities between countries are caused by the unequal distribution of power, income, goods and services, globally and nationally, the consequent unfairness in the immediate, visible circumstances of people’s lives – their access to health care, schools, and education, their conditions of work and leisure, their homes, communities, towns or cities – and their chances of leading a flourishing life. This unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a ‘natural’ phenomenon…Together, the structural determinants and conditions of daily life constitute the social determinants of health.” (WHO Commission on SDH, 2008)

- o The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has identified a simpler phrasing to describe SDH:

- “Health starts where we live, learn, work and play.”

SOCIAL GRADIENT OF HEALTH

- Life expectancy is shorter and disease is more common further down the social / socioeconomic ladder

WHAT ARE SOME EXAMPLES OF SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH?

- Education, employment opportunities, water, sanitation, housing, food access, level of social inclusion / exclusion, social support networks, stress, early childhood development, race/gender/sexual orientation/etc (as they impact the other SDHs)

WHAT IS THE RELATIVE IMPACT OF SDH ON HEALTH VARIANCE / OUTCOMES? A lot; probably more than half

- Various researchers have shown that health care accounts for only 10-25% of the variance of health over time.

- The rest is shaped by genetics (up to 30%), health behaviors (30-40%), social and economic factors (15-40%) and physical environmental factors (5-10%)

- SDH effectively create remarkably disparate health outcomes, even within the same city, county, state and country. For example:

- o Life expectancy differences-metro Washington D.C.: 72 (City Center)

- o Life expectancy differences in the U.S. 66.6 (Bennett County, SD)

EXAMPLES OF SOLUTIONS

- The case studies in the WHO site http://www.who.int/sdhconference/resources/case_studies/en/ present successful examples of policy action aiming to reduce health inequities, covering a wide range of issues, including conditional cash transfers, gender-based violence, tuberculosis programs and maternal and child health.

CENTRAL FIGURES IN WORK ON SDH:

- Michael Marmot: (1945-present) British epidemiologist and international statesman on health inequities who was a lead investigator in the Whitehall Studies of British civil servants (assessing health inequities in Great Britain) was the founding chair of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants (2005-2008); Lecturer / author of “Health in an unequal world” (Lancet, 2006; 368: 2081-94)

- Paul Farmer: (1959-present) American anthropologist and physician best known for his humanitarian work providing health care to rural and under-resourced areas in developing countries, beginning in Haiti. Co-founder of the international social justice and health organization, Partners In Health (PIH), and professor at Harvard Medical School. Author of numerous books and publications, including Pathologies of Power.

- Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow: 19th century Germany doctor, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. Ahead of his time in pushing early advances in public health. Considered by many to be the founder of social medicine. Since disease so often results from poverty, he said, then physicians are the “natural attorneys of the poor”, and social problems should largely be solved by them.

“We pledge to bind ourselves to one another, to embrace our lowliest, to keep company with our loneliest, to educate our illiterate, to feed our starving, to clothe our ragged, to do all good things, knowing that we are more than keepers of our brothers and sisters.

We are our brothers and sisters.”

-Maya Angelou

Optional Readings:

Pathologies of Power: Paul Farmer

Savage Inequalities: Jonathan Kozol

The End of Poverty: Jeffrey Sachs

Development as Freedom: Amartya Sen

Immigrant Medicine: Patricia Walker and Elizabeth Garnett

“Why America is Losing the Health Race”, Allan Detsky (The New Yorker, 6/11/14)

“Health in an Unequal World”, Michael Marmot (Lancet 2006; 368: 2081–94)

Created by Andrew Smith, MD

Community Health Centers: A History

Link to: Preble Street Learning Collaborative

Required Readings: Community Health Centers: Leveraging the Social Determinants of Health

Care of the Homeless

Questions to Consider for Panel Participants at Day Break Shelter

- What situations led to your becoming homeless. Was it lack of money, lack of education, bad breaks, lack of support, divorce, drugs, abuse, loss of job, lack of affordable housing, mental health issues, a combination of things…..?

- Tell me about the risks for violence in the homeless situation. For example: risk for physical and sexual abuse, risk of robbery, risk of intimidation (being threatened by someone), how common is violence in the shelters or rooming houses(YM(W)CA,)…

- While you have been or were homeless, what troubled you most about the situation? For example: fear of others, hopelessness of ever getting out, worsening medical problems, worsening addiction, lack of good food, lack of family, lack of transportation, lack of access to health care.

- Who and what services have helped you most? For example: services offered at DayBreak and The Psychological Center, friends, drug programs, medical services, bus passes, vouchers for cabs, taxi and buses, help with getting MassHealth…

- In your experience, how easy is it to get and maintain housing?

- In your experience, how are children affected?

- Do any of you have questions for all of us here i.e. health care workers in attendance today?

Reading: Care of the Homeless: An Overview

10 ISSUES TO CONSIDER WHEN WORKING WITH THE HOMELESS

BE RESPECTFUL: Many of our friends are victims of violence and as a result trust levels are low, especially with the healthcare system, are low. Be respectful and in awe as to how they survive.

WITHHOLD JUDGEMENT: Withhold judgment with respect to what appear to be horribly adaptive behaviors on the street with relation to drug abuse, crime …until you’ve walked a day in their shoes or at least listened to them for 6 months.

MODIFY THE GUIDELINES: Modify your guidelines and evidence based medicine to fit the realities on the street. You wouldn’t want to give a diuretic to someone who has no access to a bathroom and who must urinate in public, a criminal offense.

CONTACT INFORMATION: Make no assumptions. Simple things such as contact info can be challenging for homeless. Instead of saying, “What’s your phone number?”, consider a more sensitive questions such as “Is there a way we can get in contact with you?” or “Is there anyone who can reach you?”

FOOT CARE: For people who spend much of their day on their feet and who may not have access to clean socks on a daily basis, foot care becomes much more challenging. Whenever possible, do a good foot exam…and consider carrying around a few extra pair of socks

IDENTIFICATION AND INSURANCE: Although most homeless people are poor enough to qualify for public health insurance, the transient homeless encounter extra issues with identification and addresses. If state ID is lost or stolen it can take a long time to get back into the system and back on insurance

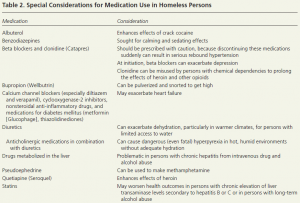

MODIFY THE MEDS YOU PRESCRIBE: Be aware of potential dangers associated with meds below (among others)

KNOW WHEN PEOPLE HAVE MONEY: Most state and federal assistant programs provide funds to people at the beginning of the month. This can create a dichotomy of experiences depending upon the time of the month. Some people will choose to stay in a hotel room or be more active in drugs at the beginning of the month when they have some cash on hand. Conversely, some may run short of food or other public entitlements by the end of the month.

GET TO KNOW YOUR PATIENT’S NARRATIVE: Get to know the individual in a laid back, open-ended manner. Try to learn about the individual’s personal narrative, including where he/she is from, how long he/she has been homeless, and what life circumstances may have led to an unstable housing situation. Show empathy and understanding, while not pushing an agenda.

MOVE AT THE PATIENT’S PACE: Client readiness is imperative to successful engagement. If a client is not ready to engage—for a host of reasons, including fear, lack of trust, or mental illness—he or she has the power to decline. Continue to show support and a consistent presence, and clients may eventually become willing to engage. Have an open dialogue with clients regarding pacing to ensure that you are working at a comfortable speed.

Sources: Vince Waite, MD – GLFHC, Cara Marshall, MD – GLFHC, Andy Smith, MD – GLFHC, Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(8):634-640, National HCH Council